The Case for Holding Japanese Equities (est read time: 5 mins)

Bryce Anderson , Portfolio Manager, Asia Pacific

Clémence Dachicourt, Portfolio Manager, Europe, Middle-East & Africa

- Japan has endured a remarkable period of economic stagnation, but the future looks brighter.

- A legacy of poor corporate governance hampered Japanese equities, although this is improving. As a result, dividends and buybacks continue to improve from a very low base.

- The fundamentals are reasonably sound. The deleveraging cycle appears to be halting, while corporate profitability in Japan is at 20-plus year highs. Amid the structural reforms, if the banks can find a way to lend more, we see opportunities for upside.

- The valuations are still cheap, especially among Japanese financials. Taken together, we like Japanese equities from current levels and assign a “Medium” conviction.

The lost decades in Japan have become one of the defining investment stories of our time. From its 1989 highs, the country endured a sustained period of weak economic growth with intermittent recessions and periods of deflation that resulted in stagnant economic growth. Asset price deflation accompanied these economic woes, and both equities and residential property remain below their 1989 highs.

This has created a fascinating situation, with an extended period of stress and many false starts. In an attempt to end the ongoing trauma, promote growth and counteract the deleveraging in the private sector, the government of Japan increased leverage significantly to become one of the world’s most indebted countries (with a debt-to-GDP ratio at over 200%). Only recently has corporate leverage finally returned, perhaps enabling the government to ease its own debt issuance.

The question is whether Japan is ready to turn the corner—both economically and in the markets. While the relationship between the two is often tenuous, Japanese equities remain relatively unloved and could be an attractive long-term position as well as offering diversification benefits. This is especially true if Japanese companies can sustain their profitability growth, which has turned the corner after a few poor decades.

To assess the potential for improved profitability, one must acknowledge what went wrong and why. One of the most-cited problems was weak corporate governance, which resulted in poor dividend policies, obscure compensation schemes, a lack of appropriate risk-taking, a very low percentage of independent directors and high cross-shareholdings, making merger and acquisition activity problematic. Japanese companies also failed to target appropriate profitability metrics, leading to high cash holdings and a general perception that they don’t always act in the best interests of shareholders. As such, investors have priced in a valuation discount relative to global peers.

So, what is going on and could we expect a change?

With so many underlying issues, investors have been yearning for a catalyst. Regarding profitability, in 2012, along came Abenomics and the so-called “Third Arrow”, as Prime Minister Shinzo Abe tried to stimulate economic growth and address some of the profitability issues that have plagued Japanese companies. As a part of this response, Japan’s Corporate Governance Code—aimed at reversing poor corporate governance practices—came into effect on June 1, 2015.

Sceptics were quick to question whether the government could influence the fundamental structure that had held back corporate Japan for so long. For example, in Japan very high corporate cash holdings were associated with a low percentage of independent directors, but it wasn’t clear whether government regulation would meaningfully shift that cash into shareholders’ pockets.

Now several years into Abenomics, we’re able to see some clear positive developments. One of the most encouraging has been profitability targeting by corporate management, which has increased rather dramatically.

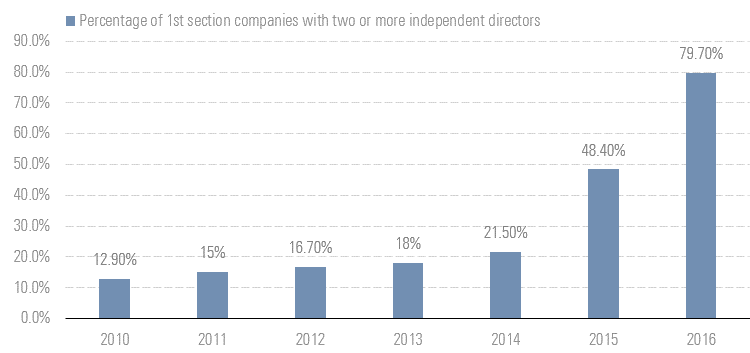

As intended, independent directorship also increased significantly, with the Corporate Governance Code acting as an effective method for change. This was undoubtedly encouraging, but it is worthwhile remembering that it will only be helpful if it drives outcomes such as increased payouts to shareholders.

Chart 1 The changing structure of company management is also encouraging

Source: JPX Tokyo Stock Exchange

In respect to payouts, dividends in absolute terms have increased across the board and payout ratios have grown significantly. In addition, buybacks (which only became a legal practice in 1994) have grown in popularity, as the number of companies initiating their first buyback program continues to increase. We believe that these developments are likely to be structural and profoundly important for investors, although wouldn’t be surprised if it is slow-moving progress.

Are Japanese financials the key?

The last piece of the puzzle is valuations, which continue to trade at a discount to global peers. Much of this is driven by the large caps, especially financials, which is a segment we find appealing. This sector has been plagued by some of the aforementioned problems in Japan—the deleveraging and deflation following excesses of the past—which has left the sector with a lot of upside.

We note that financials are largely a function of the economy, with a reasonable portion of its profitability attributable to lending (either via credit growth or net interest margins). Fundamentally, this may remain a constraint to price growth, although could offer upside if corporate deleveraging reverses.

However, quite a large part of the financials opportunity is sentiment. Valuation multiples among Japanese financials are some of the lowest we have seen and appear to be factoring in bleak times well into the future. Whilst it is not likely Japan is going to grow rapidly, we just don’t think the market appreciates many of the structural changes underfoot.

Of course, there are other influences which must be considered too. For starters, currency trends have played their part, with the Japanese yen enduring volatility. Industry concentration also remains low across the Japanese corporate landscape and whilst some evidence of consolidation is apparent in pockets, the level of M&A is not widespread.

Yet, regardless of how one views it, there are likely two key pillars that make Japanese financials a potentially enticing opportunity:

- The fundamentals are reasonably sound. The deleveraging cycle appears to be halting, while corporate profitability in Japan is at 20-plus year highs. Amid the structural reforms, if the banks can find a way to lend more, we see opportunities for upside.

- The valuations are still cheap. If investors realise the demons of the past are behind them, we may see a re-rating of these companies which would offer upside.

Assessing our conviction

With positive developments evident in the Japanese corporate sector, we must consider how much is priced in and whether holding Japanese equities is complementary in a portfolio context. To do so, we employ our four pillars of conviction, which is our way of considering the holistic opportunity under a long-term, valuation-driven framework. In this regard, we want to address: 1) the absolute expected return, 2) the relative expected return, 3) fundamental risk, and 4) contrarian indicators.

Looking at these together, we find that Japanese equities look reasonably attractive – with valuations that look encouraging compared to other key markets. The financials sector also lines up well with other opportunities such as European telecommunications, providing reasonable forward-looking prospects and a profile that offers diversification benefits to investors. From a fundamental risk perspective, there is still some volatility in the cash flows and some concerns that profitability is at a cyclical high, tempering our enthusiasm somewhat.

Overall, we view Japanese equities as a “Medium” conviction opportunity, reflecting developments that continue to be both captivating and compelling.

This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Distribution Team on 02 9276 4550.