Crisis or opportunity? 3 Simple Ways to Think About Markets Today

by Daniel Needham, Global CIO and President, Morningstar Investment Management

Key Takeaways

- Portfolio falls are temporary moves that become permanent losses only when investments are sold.

- Market volatility can be an investment opportunity for long-term investors.

- An individual’s investing success shouldn’t be measured by beating the market; it’s about being on track to achieve your goals

COVID-19 has brought massive short-term changes to our world, economy, and markets. As we look back on quarter one of 2020, there’s a dizzying amount of data and information to digest and understand. To simplify, we’re offering a few key points about markets we think advisors and investors

should keep in mind about markets, despite the unusual times we’re in.

Selling Locks in Losses

Falls in portfolio values don’t become losses unless you sell when markets are down. Faced with this, you might expect all investors to stay the course, however this is often easier said than done, even when we know what’s right. Our emotions can get the better of us, leading to decisions that can erode the value of our portfolio and make it hard to reach financial goals.

Conversely, investors that stick to their strategy—that is, rebalancing or behaving counter-cyclically after a market decline—tend to produce better results over the long term than medium-term trend followers—that is, those that sell after falls and buy after rallies.

Selling after a market decline locks in not just one loss, but likely two. Historically, markets have typically rebounded after a large decline. If you get out of the market, it’s very likely that you’ll miss the rebound. Missing the rebound is not just a lost opportunity—it statistically sets you up for lower long-term returns than if you hadn’t done anything.

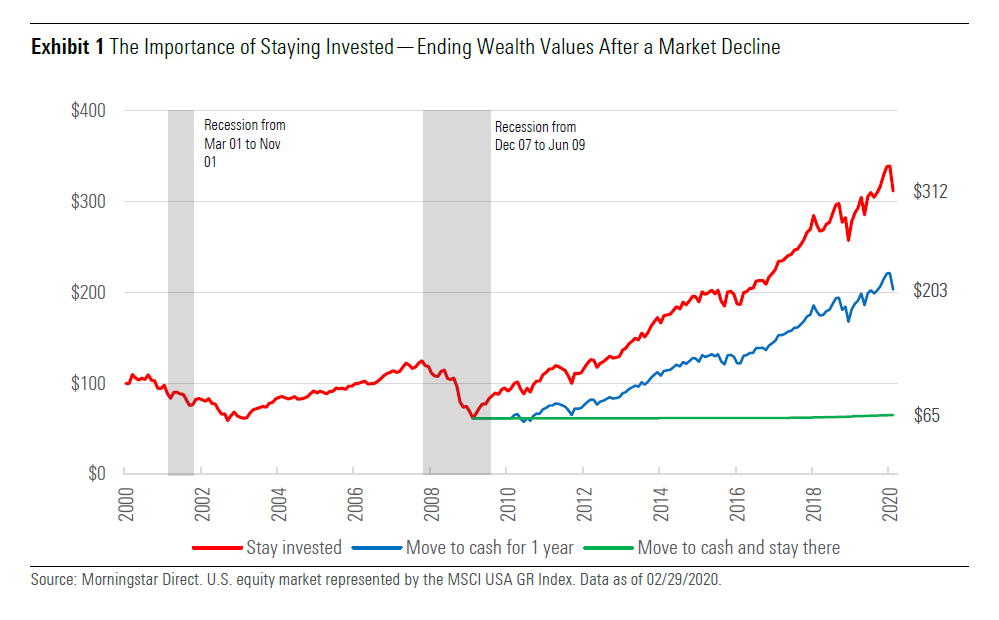

Exhibit 1 illustrates this point. It shows $1 invested in the U.S. equity market, represented by the MSCI USA Index, at the beginning of 2000. Three scenarios emerge from the global financial crisis in 2008-09: One investor holds on after the fall; one sells and waits a year before buying back in; and one gets out and stays in cash. The decision makes a significant impact on portfolio returns, with the one staying put ending with $312, nearly 50% more than the one who spent a year in cash, and almost 5 times the value of the one who got out of stocks and stayed out.

Market declines, even double-digit ones—are to be expected from time to time; in fact, the willingness

to see portfolio values move around is one reason investors are rewarded for investing over the long term. We think staying focused on the long term can help investors make better short-term decisions.

Making Lemonade From a Market Decline

For investors that think about markets in a long-term way, market volatility presents an investment opportunity not a risk. Imagine that you own a farm, and every day your next-door neighbor offers to either buy your farm or sell you his farm. Some days, when crop prices are high, he may offer you way more for your farm than it’s probably worth, and when crop prices fall, he offers you his farm for pennies on the dollar.

When prices are low and people are selling, should that make you want to sell? Should your neighbour’s depressed mood lead you to sell? Because that seems to us to be the best time to buy. A better time to sell would be when your neighbour is very optimistic and you can get a much higher price for your farm.

We think it’s the same with investment markets—they are there to serve you—to allow you to buy when prices are low and to sell when prices are high. Don’t follow the herd—they’re not looking out for you.

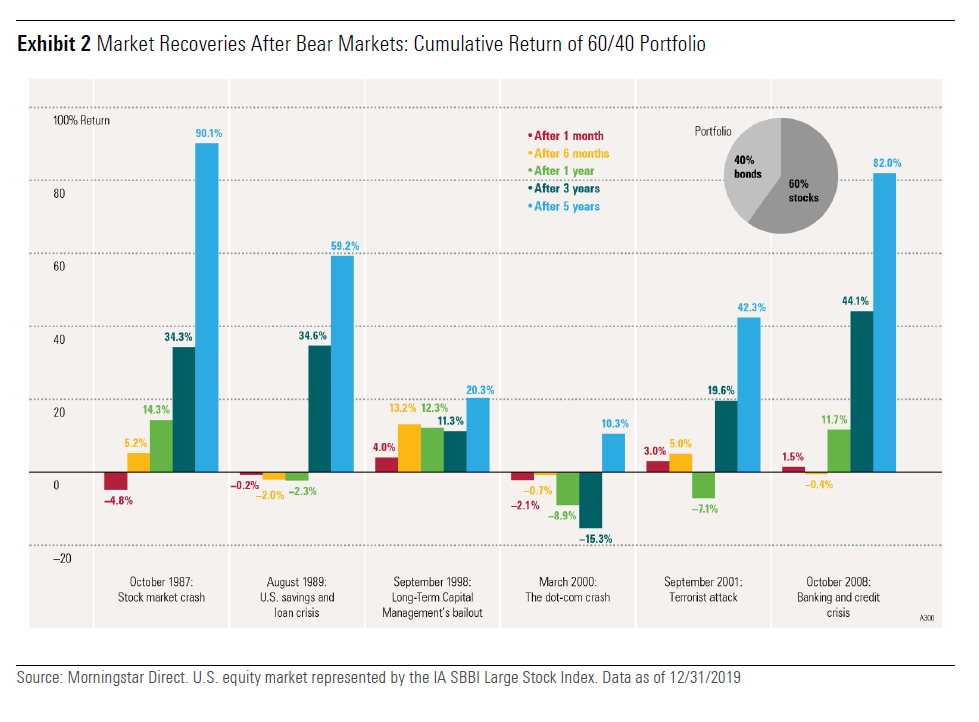

Again, looking at past market declines can give us a better idea about what typically happens in these environments. Exhibit 2 shows that the three- and five-year returns after a decline are significantly positive. Only the dot-com bubble burst was not followed by a considerable increase—largely because the global financial crisis intervened. For most, however, crises represented opportunities to investors.

Am I on Track?

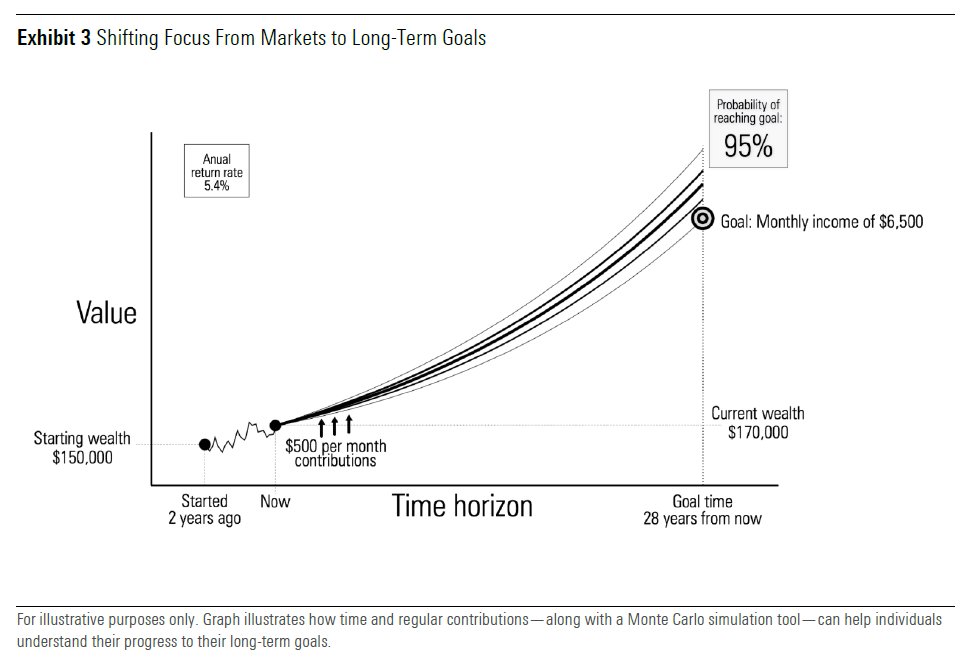

Investments are to fund goals, and for most individuals the underlying question is, “Am I on track?” A well-designed financial plan relies to some extent on investment returns. But we think for too long investors have substituted an evaluation of their investment portfolio for a sense of their progress toward their financial goals. Evaluating the investment portfolio tends to lead comparing portfolio performance to benchmarks or peer groups. This is an incomplete way to assess manager skill, but more importantly it can focus investor attention on the short term, which can ultimately destroy value if the investor switches from one strategy to the next (again, see Exhibit 1).

We think a better question is whether the financial plan itself is still appropriate for the goals that the client has identified. Bringing the conversation back to the purpose of the plan can help shift the conversation from short-term performance to achieving long-term goals.

Plans are built for volatility and with redundancy, recognizing that investment returns are uncertain. Highlighting that the investment strategy was built for this can be important and can help show that, despite short-term declines, things may be still on track.

How do most individuals measure investing success? We would expect that for most people, success is measured not by beating the market, but by being on track to achieve your goals. And staying on track, as shown above, can be a powerful way to pursue those goals.

If investors focus on these three points, we think they can make better decisions through periods of market volatility.