When We Buy Stocks… And Why (est. read time: 5 min)

“Whether we’re talking about socks or stocks, I like buying quality merchandise when it is marked down.” [1]

— Warren Buffett

Buy Low & Sell High, The Right Way

Let’s say you own a great business today and the price falls by 40% tomorrow. Should you buy more of it? All else being equal, you would be foolish not to buy more as long as your conviction in the intrinsic value of the business remains intact. Yet, the process of buying high-quality businesses at low prices is beset with behavioural challenges and something every investor must consider carefully.

Key Takeaways

- For stock investors, every buying decision requires fresh perspective, regardless of whether the stock is trading near its low or high.

- Investors need to be careful when buying stocks in certain situations. We believe structural change, rapid disruption, leverage, and poor capital allocation are all primary concerns.

- Buying into weakness often makes sense, but it is not easy and can sometimes be the wrong thing to do.

- In a portfolio context, we strive to adhere to a structured process to maximize the probability of making good decisions.

Identifying Risks When Buying Stocks

Some of the key risks to stock investors tend to cluster around the following situations:

- Industries undergoing structural change. This can evolve via comprehendible means (an ageing population or industry in structural decline) or via rapid disruption that is harder to distinguish (wiped out via technological advancements).

- The erosion of an individual company’s economic moat. A company without a durable competitive edge may benefit from a fad or it may temporarily benefit from a first-mover advantage, but will ultimately succumb to another company with a stronger competitive positioning.

- Leveraged businesses that succumb to debt constraints. Prominently, if an investment falls in price, the debt can suffocate the capital, creating the conditions for a perfectly good business to be a value trap.

- Businesses with poor capital allocation. For example, undertaking a monumental capital expenditure program when there isn’t the cashflow to support it, destroying the value of the business. Overpaying for an acquisition, especially without a strategic fit, or not reinvesting enough back into the business (research and development) could be other examples.

The other, which is likely to have relevance today, is when assets are still expensive. This may not fit the classic definition of a value trap, but an asset going from extremely expensive to moderately expensive is unlikely to make a good investment, even if the price has fallen meaningfully.

Lessons from a Classic Collapse

Some companies can appear strong on face value but tumble into structural decline. Take Kodak for example, where many investors in the 1990’s never anticipated the progression of digital cameras, nor that Kodak would be left behind in that progression. Buying in the dips would have been a terrible idea for most investors, as you would have continually bid up this exposure only to find it halve, halve and halve again.

Underpinning the above risks, a key challenge is that early and wrong can sometimes be indistinguishable in the initial stages of an investment. An investor who is early would likely prefer to increase their exposure as the probability of a turnaround increases (much like a poker player should). However, if that investment becomes wrong (a value trap), they should consider accepting their losses and moving on. It is entirely possible to be both early and wrong if the nature of the asset changes over time.

This is also a warning that cheap assets can get even cheaper, so it isn’t enough to simply buy cheap companies. We need to ensure the quality of their cashflows are sound and that they have durable advantages that allow for the benefits of compounding. For example, if a poor-quality investment falls by 20%, but could fall a further 30%, 40% or 50%, we likely want to avoid going all in.

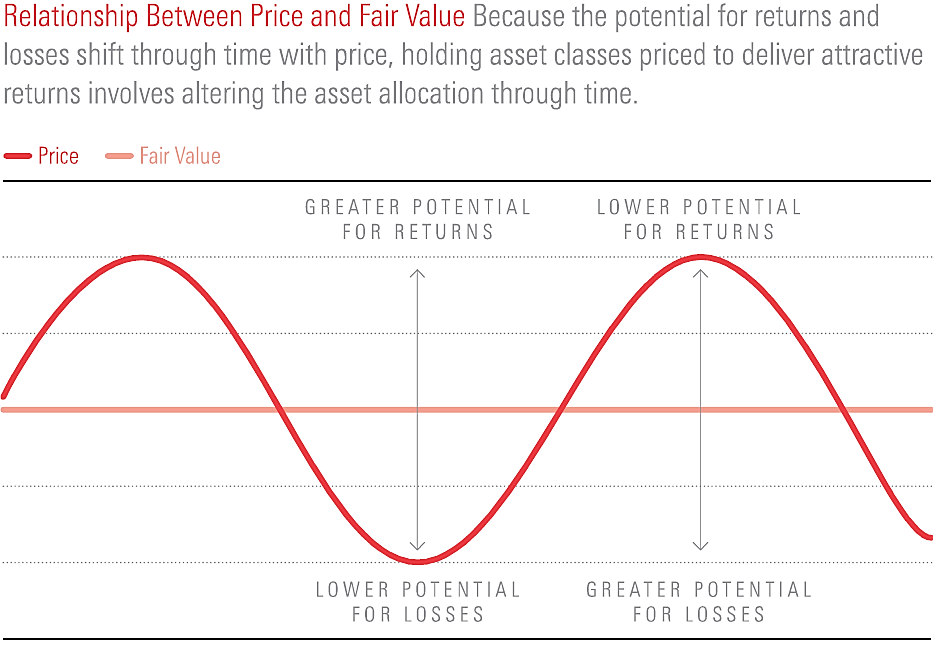

Exhibit 1 The relationship between price and fair value is the principle that guides valuation-driven investing. However, it does open potential issues regarding value traps.

In principle, if we want to buy high-quality businesses at prices below their intrinsic value, we must conform to the idea that we might be early to the party. After all, you are likely buying the investment today because it is unloved and no one else wants it (yet). By undertaking this exercise, there are no guarantees someone will want it next week, month or even year. Hence the reason value investors often cherish the word ‘patience’.

Our Process When Buying Stocks

Beyond rigorous research and risk management, we face an undeniable truth: buying high-quality stocks at a discount is not easy and we’re very unlikely to get the perfect timing on an investment. If we do, it will require a lot of luck. However, this doesn’t mean we should ignore the opportunity as valuation-driven investors.

To bring this to life, we consider the following as an important checklist. The idea behind this structure is to reduce the likelihood and magnitude of any mistakes, while giving ourselves the best chance of capturing value for our clients and delivering strong long-term returns:

A Buying Checklist

- Before executing on anything, ensure the thesis still stands. Never let behavioral traits like stubbornness, ignorance or fear sway an investment decision. This should apply no matter how uncomfortable it feels.

- Review every stock in a consistent manner. We stick to four pillars; 1) identify the absolute return we might expect to achieve, 2) judge the return relative to the rest of the opportunity set, 3) examine the fundamental risks that could prove us wrong, and 4) assess the sentiment towards that stock (contrarian indicators).

- Ensure the analysis includes a deep-dive on debt levels, capital allocation, and consider whether an industry is undergoing a period of structural change.

- Have a clear portfolio construction mandate, and where appropriate, include limits on maximum exposure. This won’t always reduce the likelihood of errors, however we believe it will help reduce the magnitude of loss. We believe portfolios should be built for multiple outcomes, not just one.

- Last, use a peer review process to vet investment decisions. This can be a constructive way to pick holes in a proposal and test the strength of the thesis.

In summary, we like buying into weakness, but only when it makes sense to do so. To our way of thinking, the only way to know if it makes sense is to conduct rigorous checks before every buying decision (such as the checklist above). The key is to leave emotions like fear or greed aside, instead focusing on delivering long-term returns that can help investors achieve their goals.

[1] Source: Berkshire Hathaway 2008 Shareholder letter