Menu

Menu

Adviser-to-client template: The expensive gap between time in the market vs. timing the market

“Just keep swimming, just keep swimming.”

Dory, Finding Nemo

As volatility in markets continues to test investor resolve, we think all investors could learn something from Dory.

This basic investment principle of staying invested sounds easy enough, but it gets trickier in practice. In our investment manager, Morningstar’s, annual Mind The Gap study, they found that on average, the actual return enjoyed by investors was 1.7% lower per year than the total return their fund investments generated over the same period*. While this may seem like a small difference, compounded over many years and into retirement, the opportunity cost is significant.

So – why the difference? Why do investors consistently leave returns on the table? To quote the findings, “Inopportunely timed purchases and sales cost investors about 22% of the return they otherwise could have earned had they bought and held.”

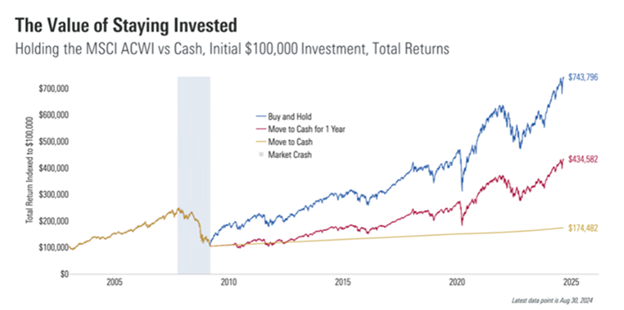

While cost, tax positions and other cash flow variables also need to be considered, the chart below helps to illustrate the importance of time in the market versus timing the market – a crucial and often expensive distinction.

Source: Clearnomics, CBOE

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. This is for illustrative purposes only and not indicative of any investment. An investment cannot be made directly in an index. References to specific asset classes should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy or sell any specific security in those asset classes.

Investors who attempt to time the market run the risk of missing periods of positive returns, which can lead to significant adverse effects on the long-term value of a portfolio.

The chart above illustrates the value of a $100,000 investment in the stock market during the period 2005–2024, a period which included the Global Financial Crisis (the grey highlight) and the recovery that followed. The value of the investment dropped back to around $100,000 by February 2009 (the trough date), following a severe and protracted market decline. If you remained invested in the stock market until the end of August 2024, however, the ending value of your investment would be around $743,000. If you chose to exit the market at the bottom to invest in cash for a year and then reinvested in the market, the ending value of your investment would be around $434,000. An all-cash investment from the bottom of the market would have yielded an end value of only $174,000. While all market recoveries are not equal and may not yield the same results, staying the course has historically proved to be the best option for patient investors and removes the difficult decision of when to re-invest from the sideline.

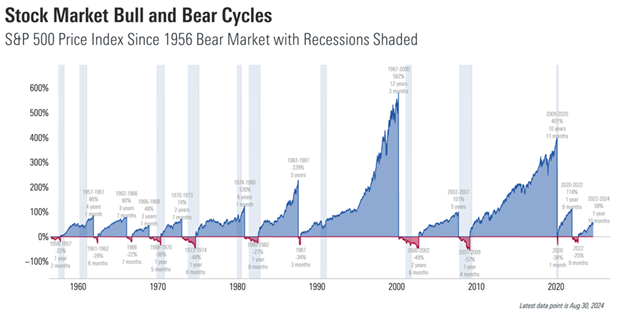

A final point to make is that it pays to see the glass half-full when investing. The graph below represents the S&P 500 Index which stands for the Standard and Poors 500 Index, an Index of 500 large companies listed on the US stock exchange.

Source: Clearnomics, CBOE

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. This is for illustrative purposes only and not indicative of any investment. An investment cannot be made directly in an index. References to specific asset classes should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy or sell any specific security in those asset classes.

While enduring the recessionary periods (the red) are painful in the moment, history shows that eventually, all bear markets have found a trough, paving the way for subsequent economic expansion and more bullish recovery. These phases of the economic and market cycle are not created equal. As the chart above shows, bear markets since 1956 have lasted anywhere from 6 months to two-and-a-half years. During these periods, the U.S. stock market has fallen anywhere from 22% (1957) to 57% (the 2008 financial crisis) at their worst points.

In contrast, bull markets (in blue) have lasted from about 2 years to over a decade in length, with the two longest cycles occurring during the past 30 years. The eleven-year bull market that ran from 2009 to 2020 experienced a price return of 401% and close to a 530% return with dividends re-invested. Investors who stayed the course once again came out on top.

So, in the face of market volatility, and the next inevitable market correction, Dory’s motto reigns supreme. Or, if you need a reminder from Warren Buffet, Chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway: “The stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient.”

If you have any questions about this note, or about your investments generally, please feel free to get in touch – I’m always happy to chat.

[Adviser name]

*Mind the Gap 2023. A Report on Investor Returns in the United States. (2023). pp.1–18.

Disclaimer

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

Cybersecurity essentials for financial advisers and practice owners

By Ivon Gower, Director of Financial Planning Products, Morningstar Australasia Pty Ltd.

- Prior to an Attack: Begin by understanding and mitigating potential risks. Preparing your staff with precise protocols to follow during an attack is essential—this proactive measure ensures that everyone knows their role and minimises the risk of chaos. Forethought is key: avoid formulating your strategy in the heat of the moment.

- During an Attack: Having a well-structured response plan in place is imperative. Equip your team with the knowledge of how to handle the situation effectively. Remember, in the midst of an attack, calm and well-orchestrated actions can save the day

- Post Attack: The aftermath calls for swift recovery. This phase is not just about restoring your business, but also elevating your cybersecurity readiness and potentially using your cybersecurity insurance.

This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 1800 951 999.

Are your clients preparing for retirement? Here’s what they should watch out for

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. In this case, preparing your clients for common sticking points as the get ready to retire can save both stress and money.

Decades spent in accumulation mode can make even the most financially savvy retirees ill-equipped to enter this new phase of life. Christine Benz, Morningstar’s Director of Personal Finance, has seen it happen. “Even retirees who are seasoned investors will tell you that transitioning from accumulating to spending from their portfolios is a challenge,” she says. Not to mention the obvious behavioural challenges that come with a dramatic change: “There are also psychological hurdles to jump over: After years of saving, transitioning into drawdown mode can feel a little bit scary.”

So how do you, the adviser, ensure your clients are in a good position to forge ahead in their retired life? Here are four key points to check off with your client.

![]() We’re living longer

We’re living longer

As time ticks on, life expectancies are growing longer. According to Philip Petursson, Chief Investment Strategist and Head of Capital Markets research at Manulife Investment Management, research by the World Economic Forum has found a person born in 1947 during the post-war baby boomer generation would have an average life expectancy of 85 years. If you were born 30 years later, that expectancy jumps almost a decade – to 94 years.

Longevity risk is arguably the dominant risk for today’s retirees. David Blanchett, Morningstar Investment Management’s Head of Retirement Research, points out in his report ‘The Retirement Mirage’:

“Choosing when to retire is one of the single most important financial decisions we make in our lives. Knowing when we plan to retire helps determine how much money we need to save and our standard of living in the meantime.”

“Unfortunately, our retirement plans are often wrong. People retire earlier than expected for a variety of reasons—including health issues and job changes—but the impact can be severe.”

This is exacerbated if your client retires earlier, lives longer, and increasingly, was born later. Petursson notes that someone born in 1947 would need roughly 50 per cent more capital than a person born in the previous generation, and someone born in 1977, would require an extra 30%.

With the longevity risk comes a shortfall risk: the possibility of outliving one’s savings. In fact, to cover for the longevity and shortfall risks, and considering that 94 years is an average life expectancy, a retirement plan should be developed with the expectation of the client living to 100. “That’s what I calculate for,” says Michelle Munro, tax and retirement expert at Fidelity Investments.

A recent survey of 1,929 respondents by Fidelity (Retirement 20/20) shows that only 17 per cent plan that far out. The largest cohort (53 per cent) plans between 85 and 95 years of age, and 28 per cent plans between 70 and 80 years of age.

“Our findings suggest that given this uncertainty around retirement age, some investors may need double their current savings to achieve their retirement targets. A person’s retirement age is simply too unpredictable, and we must plan accordingly to help avoid negative surprises,” Blanchett says.

![]() The health curveball

The health curveball

The other major blind spot of retirees is health care and assisted-living costs.

“You often read about all the money you’ll save when you’re no longer working–on dry-cleaning, commuting, lunches out, and not having to save so much for retirement anymore, says Benz.

“Given that cavalcade of savings, it’s not surprising that so many retirees fall back on the conventional wisdom that they’ll only need to replace 80 per cent of their income during their working years when they actually retire.

“In reality, that 80 per cent rule is at best a rule of thumb; some retirees actually spend more than they did while they were working, while others spend much less. (Healthcare costs are one of the biggest wild cards).”

One area where expenses can explode: intensive care for the last period of one’s life, which could range from a few months, to a few years. “That is a huge expenditure,” highlights Munro, adding that the last third part of one’s life will probably not be a beach party.”

From 1994 to 2015, life expectancy at birth of males rose from 75 to 80 years, indicates a 2018 StatCan report, but health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE) went from 65 to 69 years. For women, life expectancy at birth increased from 81 to 84, years, and HALE, from 68 to 70.5 years. Men have to plan with the potential of about 11 years of health complaints; women, with 12 years.

Among the six health attributes of mobility, pain, sensory, dexterity, emotion and cognition, mobility stands out as the more important source of diminished health for males, while for females, it is mobility and pain.

![]() Asset allocation ‘rules’

Asset allocation ‘rules’

Many people talk about a simple rule of thumb: 100 minus Age = Equity. Put another way, if you’re clients are 70, 70 per cent of their portfolio should be in bonds.

But that is not practical anymore. “Historically low interest rates cause revenue on ‘safe’ investment grade bonds to be insufficient to generate revenue for many retirees,” says Petursson.

“Today, our capital in retirement still needs to generate a return, yet it’s harder and harder to generate a return with interest rates. The challenge for retirees is to find asset categories that will still generate return while not inordinately increasing risk.”

To mitigate that risk, it appears that coming retirees plan to continue working beyond retirement. Blanchett calls delaying retirement a ‘silver bullet’. “You’ve got one more year to save, one more year for your assets to grow, one less year to plan for in retirement. So, it’s really, really good,” he says.

![]() The planning blind spot

The planning blind spot

The Fidelity survey clearly points to a potential area of hardship: neglecting to devise a retirement plan. Asked about their level of financial preparedness for retirement, 94 per cent of retirees who have a plan claim that they feel prepared, but only 72 per cent of those without a plan claim as much. Among pre-retirees, the difference is sharper: 78 per cent of those with a plan say that they feel prepared, but only 44 per cent without a plan say so.

Munro insists that such planning should preferably be carried out with a professional – that’s where you come in. But your clients shouldn’t limit their plans to financials only. Key areas of retirement to consider are one’s social and emotional health. It’s now an established fact that people who have strong networks of relatives and friends age better. Let’s drink to that! But not too much…

For more information about our retirement tools and portfolios, and how we can help you support your clients as they transition to retirement, contact your Adviser Solutions Manager.

This article has been re-written for an adviser audience. You can read the original, by Yan Barcelo, here.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

Disrupt your own practice

Baz Gardner’s advice in Growing your practice: How to set yourself up for success, the second session of Morningstar’s 2020 Practice Optimisation Forum, struck a chord with time-pressed advisers. The three key strategies: value proposition, aligning value to fees charged, and building a steady pipeline of high-quality referrals delivered some immediately implementable opportunities for advisers to question and build on their day-to-day practises.

In a poll run at the beginning of the session – What is the biggest internal hurdle you face in growing your business? – advisers were evenly split across three answers:

- Spending time with the right clients

- Our revenue/ fee structures

- Consistently demonstrating value to our clients

Whilst not surprising answers to Gardner, he was keen to explain how interconnected these issues are. Working through these issues are fundamental building blocks to driving growth in any advice practice.

Value proposition: never done and continuously improving

A value proposition doesn’t stand alone and Gardner suggests it’s the most important thing to get right.

“Your value proposition is never done. It should continue to get better. Once a firm thinks they’ve got it right, is when we see stagnation set it.” It’s an opportunity to keep improving and perfecting how you articulate the value you add to your clients.

Some of the simplest changes can drastically alter the profitability of a business; for example bringing to the forefront the ‘implied value’ of what you provide clients. As advisers, it’s crucial to have a general value proposition when you begin your engagement, becoming an increasingly more specific value proposition as a prospect becomes a client. Key to this is exploring their objectives, needs and wants, to really get to know what they hope to achieve. Gardner noted that this element of relationship-building hinges on specific, emotionally resonant language, and appeals to the truly human needs of a client beyond returns.

Part of developing these targeted value propositions is accountability, and the partnership nature of the advice relationship. Being not just a sounding board but a source of objectivity is foundational to the success of an adviser-client relationship – which includes setting and managing transparent expectations from the start. “We’re professional nags and we’re going to protect you from bad decisions – we expect you to take it seriously,” Gardner said. As a result, he emphasises the importance of establishing what kind of partnership style your prospective clients expect from their adviser – a key step in engagement sequencing that sets the tone for the rest of the relationship.

Pricing models: every adviser I’ve met underestimates the value they provide, it’s just a case of by how much

What’s a good pricing model? Gardner suggests “one that charges enough, with the right people.” And one that allows for the charging of additional value with additional commercial exchange. This means a profitable, sustainable practice with sufficient price tension, therefore allowing adding value where possible. What a sustainable pricing model shouldn’t do is surprise a client.

If you were having a pool built in your garden and the contractors hit bedrock, they wouldn’t carry on regardless. There would be a consultation, an option to continue or not and a clear disclosure of the additional cost. Complexities and additional work as part of the advice process is no different. That’s why having a clear pricing structure and fully briefing clients before they agree to a service not only allows for a clear articulation of value and services, but establishes and maintains trust as well – leading to longer, richer client relationships.

Gardner suggested a base retainer fee to be set and charged annually, particularly in light of the Hayne Royal Commission. Importantly, he also noted that advisers should at charging additional fees where they deliver additional value: ensuring clear benefits for both parties. Again, he noted that explicit clarification of what fees are charged for is integral to ensuring happy clients.

Referral pipeline: your business – an expression of you

Finally, Gardner spoke about how to grow a client base and finding the right clients. Rather than simply looking for potential paying clients, he looks at potential clients whose goals and values are aligned to how he delivers advice – therefore enabling you to serve more clients, better. “Meaning is one of the five things I value most in my life,” he said, “so my relationships need to have meaning.” In creating these deep relationships, word-of-mouth referrals from highly engaged clients can become a key source of organic growth – in Gardner’s estimation, 2-3%.

Baz suggested adopting a ‘go-maybe-no’ traffic lights system to consistently ensure you’re focusing on clients most likely to result in successful, fulfilling, long-term relationships.

And if you’re getting all these moving parts right, here are some final words from Gardner: “the money that they pay you will never come anywhere near close to the value you’re creating, and the impact on their lives.”

This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 1800 951 999.

The changing nature of active management

by Daniel Needham, Global CIO & President, Morningstar Investment Management

Key Takeaways

- Active management may not be in decline, rather the type of active management is changing to benefit active asset allocation. This presents investment opportunities for long-term asset allocators.

- Research shows that investors need to not only be active to outperform; they need to be patient.

- Long-term investing can be psychologically challenging, so it’s important investors have an adviser to keep their focus on what really matters.

All Investing is Active Investing

The move to passive investing has been a powerful trend, but to date has focused on security selection. In this context, passive refers to the replication of a market capitalisation-weighted index, while active may describe everything else. The same principle may apply to asset allocation, with passive classically defined as holding the entire investable market in proportion to the abundance of each part.

Clearly, few, if any, investors proportionally own every investable asset.[1] Therefore, almost every investor is active on some level. Furthermore, replicating an equity index such as the S&P 500 is therefore not strictly “passive” since trading is required to match the constituents of the index[2]. In this sense, the connection between buy and hold investing and passive investing can be misleading.

When we look at how assets are invested through more accurate definitions, we believe the share of actively managed assets hasn’t declined, as much as shifted, from security-selection to asset allocation.

That is, those buying exchange-traded funds (ETFs) aren’t buying them for keeps. They’re using them to express an active investment decision (sometimes to meet a client need) and often trading them frequently, invalidating the term “passive.”

On balance, this shift in active management increases the opportunity to outperform, we believe, for investment managers who are able to take broader views on asset classes, sectors, industries, and other characteristics. In turn, this may increase the opportunity for investors who are patient.

Shorter Time Horizons Hurt Investors

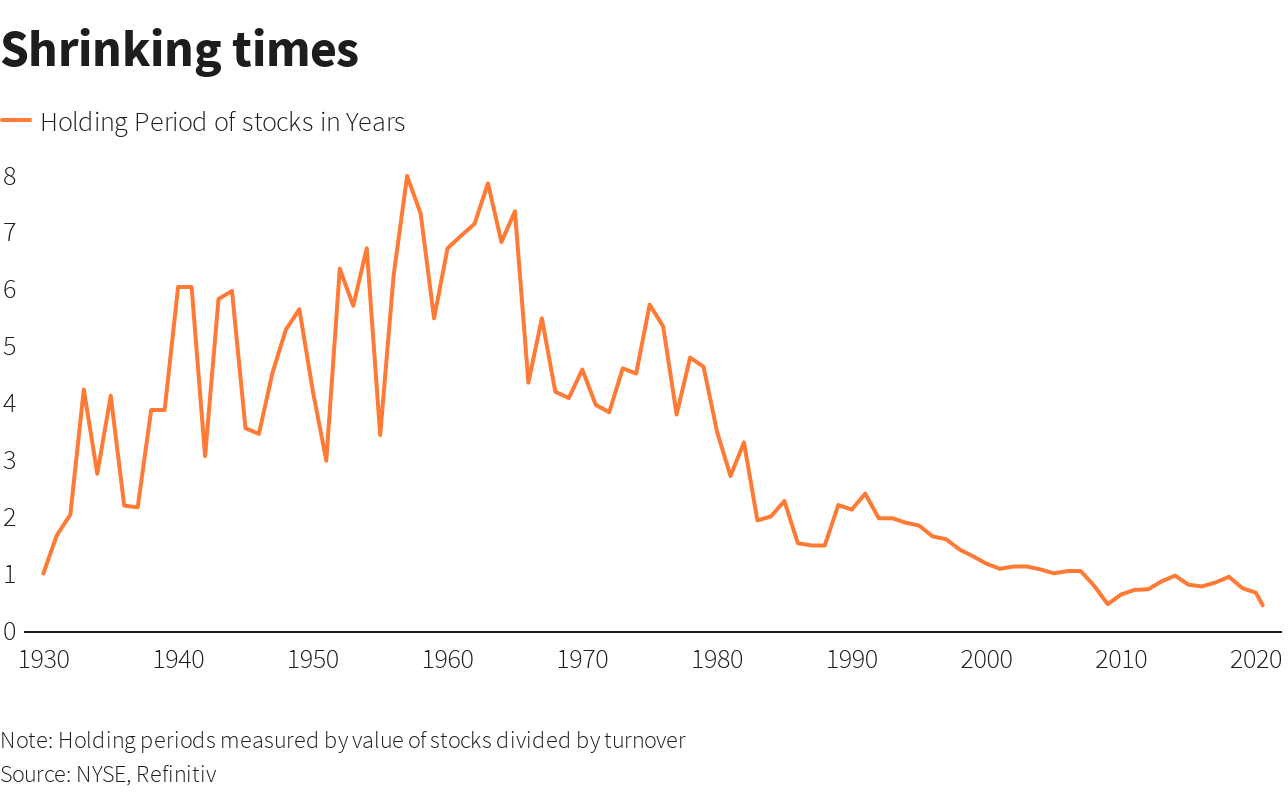

Time horizon turns out to be critical for taking advantage of investment opportunities for truly active management and receiving the benefits of compound interest—benefits that are hard to overestimate.[3] Yet, this observation contrasts with the fact that average holding periods continue to fall. Holding periods have arguably been shortened by the rise of passive management, which appears to be a contradiction given passive funds’ low turnover rates.

Exhibit 1: The reduction in holding period. Source: NYSE, Refinitiv. Note: Holding periods measured by value of stocks divided by turnover. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-short-termism-anal/buy-sell-repeat-no-room-for-hold-in-whipsawing-markets-idUSKBN24Z0XZ

If index-tracking holdings aren’t frequently buying and selling stocks, how could they contribute to shortening horizons? Because they themselves are being bought and sold. With the rise of lower-cost investment vehicles that can be traded like individual stocks, ETF volumes have risen to meaningful proportions of the market activity relative to their size. Still, it has been estimated that only about 10% of ETF volumes leads directly to the creation/redemption of shares.[4]

Despite this, it does appear that this turnover and activity impacts the underlying securities,[5] with higher volatility and turnover for stocks included within ETFs amplified by arbitrage activity—often impacting sectors, countries, industries, styles, or themes.[6]

This presents an opportunity, through active asset allocation of sectors, industries, and countries across equity markets, and for bottom-up investors that can take more active risk by including focused exposure to these areas. While the game may be getting harder in the more narrowly defined subsectors, it may be an opening for those with a long time horizon and a high active share.

By Definition, You Must Do Something Different to Outperform

According to Sir John Templeton, one of the great investors of the 20th century, it’s impossible to produce superior performance unless you do something different from the majority.

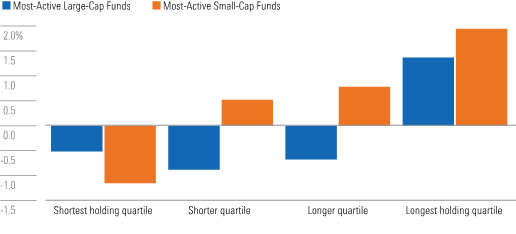

Academics call this “active share,” which is loosely defined as how different an investment strategy is from its benchmark. High active share should not be interpreted as having a higher likelihood of outperformance on its own. Like all things, one should be cautious in drawing conclusions from a single metric. On this point, author and academic Martijn Cremers[7] identified that funds with high active share and low turnover tended to do better on average. This makes sense to us.

Exhibit 2: More-active strategies held for the long run tend to outperform. Source: Cremers, M. 2016. “Active Share and the Three Pillars of Active Management: Skill, Conviction and Opportunity.” See online appendix at https://papers.ssm.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id-2891047

In our opinion, while certain strategies with lower active share and higher turnover can and do outperform, for fundamental investors time horizon seems to be the road less travelled. This concept of patient capital has been described as time horizon arbitrage and is tied to the idea of limits to arbitrage. In other words, patient investors may reap rewards—these rewards are available to any investor, but in practice go to only those who do what it takes.

Arbitrage Comes in Different Forms, Including Time Horizon

Arbitrage typically refers to different prices set for the same asset, a condition that generally requires not enough market participants seeing the big picture. The astute investor can buy at the lower price and sell at the higher one, keeping the difference.

Once, arbitrage involved buying something (gold, for example) at a lower price in one port, and sailing it to another port to sell at a higher price. With a large enough spread (and trustworthy enough sailors), anyone could take advantage of the price difference, but of course not everyone did.

Time horizon arbitrage is the idea that many investors are so focused on the short term, with lots of competition for investment results, that they don’t see the big picture, in this case the value of the investment for a long-term owner. Whether due to incentives or to psychology or career risk,[8] there’s a reluctance to extend one’s horizon. With all the focus on winning over the short-term, this reduces the competition for information that is only relevant over the long term.

While there are no doubt opportunities over short horizons for talented investors and traders, as the time horizon extends, competition appears to decline. The desire or need for quick results is the siren song for most investors. This presents an arbitrage opportunity for those willing to tie themselves to the mast and wait patiently for potential returns.

Bringing It All Together

While headlines decry the decline of active management, we may be seeing a change of active management from purely security selection to active asset allocation. This utilises portfolios of stocks, principally ETFs, rather than the underlying stocks themselves. The rise of passive management may imply less activity and longer holding periods, however the opposite may be occurring.

With the rise of active asset allocation through ETF trading, we see an opportunity for asset managers willing to be different, taking a long-term view. As the security selection asset manager universe shortens their time horizon and increase their activities, the opportunities may well be in doing the opposite—fishing where the fishermen aren’t.[9] Reinforcing one of the few durable investment advantages—a long-term investment horizon.

We think this changing nature of active management is therefore an opportunity and an advantage for us at Morningstar Investment Management. Our investment process is designed to opportunistically buy assets and patiently hold them until they appreciate. At times this means that we are well out of step with markets as we wait for prices to return to their long-term fair values, but we believe that we will significantly help investors meet their goals in the long run.

Of course, we can’t do this without their help. Changing strategies midstream can destroy value for investors because it often means selling low and buying high—something commonly referred to as “chasing returns.”

Financial advisers can help clients stay the course by reminding them of the big picture and keeping their focus on the long term.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/25/magazine/should-you-be-allowed-to-invest-in-a-lawsuit.html

[2] “Being passive” is in fact still an active choice. As Lasse Pederson pointed out, even “passive” managers of indexes are required to trade[2] due to buy-backs, dividends, re-constitutions and corporate actions, often with active investors on the other side. This isn’t talked about often but could be argued as a potential source of alpha. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2469/faj.v74.n1.4

[3] Albert Einstein supposedly said that compound interest was the eighth wonder of the world, and even modest returns compounded over very long time periods turn into large sums. Legendary investor Warren Buffett said his life has been the product of compound interest.

[4] In the BlackRock’s October 2017 Viewpoint, they point out that the average creation/redemption was 11% of secondary daily ETF flow and 5% of all US stock trading.

[5] https://www.troweprice.com/content/dam/ide/articles/pdfs/2019/q3/the-revenge-of-the-stock-pickers.pdf

[6] This potentially increases non-fundamental information and reducing efficiency. The more trading of baskets of stocks via ETFs, the more this can impact prices of the underlying basket of stocks. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w20071/w20071.pdf

[7] Who coauthored a 2009 paper that introduced the active share concept, and identified in a 2016 paper the relationship between active share and holding periods.

[8] The challenge is that most arbitrageurs manage other people’s money, and the fund manager may be fired before their long-term investments deliver results. The irony of the lack of competition for long-term investment ideas due to the institutional limits to arbitrage is that the benefits of compounding returns is best over very long horizons.

[9] An expression that’s a clever contrarian twist on Charlie Munger’s advice to fish where the fish are, borrowed from Jeremy Hosking, an outstanding investor of the eponymous Hosking Partners LLP.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

How can advisers help clients through market anxiety?

The market volatility in the second half of 2020 can make even the most seasoned of investors cautious.

Hesitation to trade during a downturn, however, creates an interesting dilemma: Investors are afraid to lose money, yet downturns can provide great opportunities to buy stocks at a discount. So, how can advisers help their clients calmly and thoughtfully evaluate when to buy? We believe that proper framing–how advisers describe a situation–can play a beneficial role.

3 approaches to calming investors’ market anxiety

In our experiment, we sought to understand how market downturns can affect investors’ decision-making. Specifically, we were interested in whether particular pieces of advice from a financial adviser could differently affect investors’ engagement with the market during increased volatility.

The experiment included an online sample of 880 Americans (representative by age, gender, and ethnicity), and took place in late May 2020–as markets began to calm.

The experiment’s design was simple. To ensure that our participants were aware of the market volatility, we had them read about the downturn of global stock markets with the onset of the novel coronavirus pandemic. They imagined receiving advice from their financial advisor on how to best manage their assets during market volatility in one of three forms:

- Historical performance, where the advisor framed the market downturn as a path to increase the value of their investments,

- Story, where the advisor framed the market downturn itself as a reason to stay in the market, and

- Opportunity, where the advisor framed the downturn as an opportunity to buy a stock at a discount.

Participants then decided on changes they’d make to their portfolios: either sell their equity investments, invest more in the stock market, or make no changes. We also included the option “make no changes due to having no equity investments” to omit non-investors (removing 105 participants). Only 48 participants decided to sell their investments (a sample size too small for meaningful comparisons), so we grouped them with those who decided to make no changes in order to form a “did not buy” group.

This study turned up three main findings:

- There’s power in seeing increased volatility as an opportunity. Most people preferred to either stay put or sell when they faced the story and historical performance conditions. Only when the situation was phrased as an opportunity did the majority of people buy additional stock.

- The active stay active. Across all forms of the experiment, participants who self-identified as active investors were approximately 2.4 times more likely to want to buy during a downturn compared with people who didn’t view themselves as investors or those who saw themselves as investors but are not making new investments.

- Emotions matter. Participants who reported experiencing positive emotions during the pandemic were more likely to purchase additional assets across all three forms of the experiment.

These findings suggest that during a downturn it may be more beneficial to help clients reframe their thinking so they feel positive about investing, rather than to simply encourage them to purchase.

Multiple paths through market anxiety

When the markets grow increasingly temperamental, it’s natural for investors to get nervous. There are, however, good reasons to weather the storm.

Our research shows that clients can benefit from market swings if they see downturns as a blessing, not as a curse. For anxious clients who have the resources to invest but remain hesitant, encouraging them to see increased volatility as an opportunity to earn a profit rather than as a reason to run can be a successful growth strategy.

This article includes research from Morningstar behavioural researcher Sarwari Das.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

Building a modern advice practice

Understanding and positioning the value of advice has long been a point of tension for advisers – arguably even more so as the financial landscape changes. Whether those changes be related to a changing client demographic, more regulatory scrutiny, or dare we say it – a surprise pandemic. Morningstar’s Deborah Graham lead this discussion in Building the Modern Advice Practice of the Future, the final session of the recent Practice Optimisation Forum.

Graham was joined by Recep III Peker (Investment Trends), Grant Chapman (Fintech Financial Services) and Phil Anderson (Association of Financial Advisers). Attendees were welcomed to the digital session with a poll that would then dictate the topic of the day: a choice between ‘making advice affordable – is there a role for scaled advice?’ and ‘the value of the technology stack’. Scaled advice had the edge with 59% of the votes, sparking a thoughtful discussion among the panellists.

Aligning value to appetite: Finding opportunities in scaled advice

Recep III Peker cited a July 2020 survey finding that people actively seeking advice said, on average, they’d expect to pay $360 for financial advice. Taking rent, overheads and other costs of running a business in account, Peker gave a ballpark figure for what advice generally costs – closer to $3000-$4000, therefore revealing significant dissonance between the perception and actuality of pricing. He suggests that scaled advice is the gateway to building a broader, comprehensive advice relationship – providing the opportunity to educate clients on the value of both advice and the advice pricing models.

“If you get personal advice, it’s like jumping into marriage straight away. With scaled advice, it’s more like dating. There are three times as many people who want to start with scaled advice, but 93% of these people are happy to get comprehensive advice down the track. Essentially, scaled advice can serve as a strong hook when it comes to addressing the affordability of advice.”

Phil Anderson agreed, but noted industry challenges that advisers may face as they seek to incorporate scaled advice in their service offerings. “Scaled advice is going to be critical to keep advice affordable for everyday Australians. Research says the unadvised aren’t willing to pay, but existing clients are paying substantial amounts of money and are getting great value out of that… we’re in a difficult position because we see a lot of opportunity with scaled advice but we need more regulatory certainty. And we need to have the opportunity for advisers to improve their processes and push forward to really rationalise the process, to add value at every stage for the client so they’ll want to come back.”

In discussing value, having a clear picture of your customer or intended audience can shape your practice. “What is your target client segment?” Grant Chapman asked. “If you’re dealing with Generation X or a younger cohort, they might be used to doing things online and getting things quite cost-effectively, you’d need an offer that appeals to them. Providing a scaled advice solution, and particularly using technology – I can’t emphasise enough how much technology needs to be integrated for efficiencies and delivery. You may use scaled advice to get initial business with a younger group, and that becomes a journey as their life evolves.”

Positioning the cost of advice

“It’s a real tension for advisers,” said Chapman. “How do we actually deliver what the client needs, whether that’s scaled advice, or where every area of advice is comprehensively addressed with a lot of cost and time involved?… We have to re-educate our clients and deliver the information to them in a way that they understand the value that’s being provided to them. I think when clients actually do see that, and go through the process of understanding, they’re more willing to pay for that advice.”

Similarly, the efficiency theme doesn’t just apply to the scaled advice realm – nor is it just about creating day-to-day efficiencies in your practice. “Right now for financial planners, the true opportunity to make money, is from your ability to retain a larger client book. So anything that makes you more efficient is really powerful. If you’re sitting behind your computer picking stocks every day, that’s time you didn’t invest in doing the client update and showing them value to invest another year,” said Peker.

How do clients want to be engaged?

Tailored communication with clients may not be reinventing the wheel, but research shows that this foundational piece remains hugely important to clients across the board. “Satisfaction with financial planners is at the lowest level we’ve observed in ten years,” said Peker. “And this isn’t because financial planners aren’t managing their clients’ investments well. If you ask clients to rate their financial planner on investment expertise and investment selection, it’s actually at a near-time high, because for a lot of people their adviser told them to stay in the market. However, what’s dragging the satisfaction score down is the piece around how frequently I get contacted, ability to explain investment concepts and so on.” Delivering financial education, engaging content and therefore creating a two-way relationship with clients has become a cornerstone of the modern advice practice.

Social media, video and intuitive online portals have been everywhere in 2020, and the advice sector is not immune to these trends. With different mediums appealing to different audiences, the panellists also spoke to how these methods can best convey an adviser’s well-thought-out messaging.

Financial planning software and emerging fintechs also rated a mention in the client engagement space: “you can really personalise the experience and make the client feel in control of the process… However, we need regulatory certainty so advisers know how to incorporate this into their processes,” said Anderson.

It’s apparent that though the methods may change, proactive engagement remains a reliable tactic that endures through industry changes. And in doing so, advisers are better positioned to plant the seeds for long-running client relationships.

This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 1800 951 999.

4 steps to mastering virtual meetings

With remote working and improved technology characterising much of 2020, you’ve like already seen an uptick in virtual meetings. And while video chatting makes these face-to-face interactions possible while still allowing for physical distance, there are some steps you can take to make your virtual meetings truly stand out—and make a positive lasting impression on your clients.

Step 1: The right technology

The software you choose will directly impact the ease of meeting logistics. Though just about every social media or communications platform has a video chat option, they’re not all created equally—and specifically, not all created for business purposes. We’d suggest looking at services like Zoom, Google Hangouts Meet, Cisco Webex Meet or Microsoft Teams, which are equipped with features like screensharing, the ability to dial in, and more. You may find that the ability to record a meeting becomes invaluable to your practise, or that you can’t live without having a chat feature to send links or references while you’re talking.

Similarly, hardware can make or break a meeting experience. A simple d headset (rather than just the built-in microphone on your computer), can increase the quality of a call ten fold and ensure a smooth meeting, with fewer bumps.

Step 2: The right environment

When you’re in an office, this work has generally already been done: uncluttered spaces and professional décor go a long way to guiding your clients’ expectations. Luckily, these are easy fixes in the home office, and only require a small space (your camera’s frame of reference). Bookshelves, art or plants lend warmth to a space, and panel dividers can be easily set up and removed if your home has turned into a multi-person office.

Lighting is also key to your clients’ overall impression. Bright light sources behind you will cast a shadow, so it’s preferable to have light sources from the front. One way to control these shadows is by mixing light sources (for example, natural light from the window, a desk lamp, and overhead lighting). You could also use an LED desk lamp to control the lighting on your face.

Another consideration if you’re not using a headset is echo. To absorb echoes, rugs, curtains and upholstered furniture can make a big difference and make the meeting experience altogether more pleasant.

Step 3: Test your setup

Join your meeting a few minutes early to ensure that everything’s working as needed. This includes testing your camera, audio and internet connection. Taking the extra step of closing or minimising unnecessary applications on your desktop will also go a long way to quickly navigating between windows during the meeting. Muting or using a Do Not Disturb feature for messaging platforms will also ensure no distracting pop-ups while you’re sharing your screen.

Sending an invite to clients with clear instructions well ahead of the meeting time can keep technical difficulties from derailing the schedule, and many meeting platforms are integrated to send these invites when the meeting is added to the calendar. You can also set these up to include email reminders and clear access instructions or a link/dial-in code to join.

Step 4: Make eye contact and engage in active listening

It can be difficult when you’re not in the same room, but eye contact is just as important – if not more – in a virtual meeting. Not only does it demonstrate presence and engagement, but can help forge a connection with your client. Many video meeting platforms have a small inset feature where you can see yourself, but it’s easy for your eyes to drift there while talking to a client. If your platform has the capability, you can disable this feature, making it easier to focus on speaking directly to the camera. You could also try attaching something small next to your webcam to keep your focus directed at it, such as small stickers or even googly eyes – whatever draws your attention.

Of course, it’s normal to be looking elsewhere on the screen when you’re reviewing documents and screensharing. Nevertheless, when you’re not walking a client through a specific document, try to look directly at them as much as possible, especially when they’re talking. Listening is paramount at the best of times, but with social distancing in play, can really make a difference to a clients’ experience.

© Morningstar Investment Management Australia Ltd (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of Morningstar International Shares Active ETF (Managed Fund) (MSTR). The information provided is for general use only. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at https://morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. You should consider the advice in light of these matters and the Product Disclosure Statement before making any decision to invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

3 key conversations to prove your financial adviser value to clients

By Samantha Lamas

Advisers face many obstacles, but when we asked them what their biggest challenge was, we quickly found that many related to one overarching theme: financial adviser value.

The graphic above shows that some of the top challenges for advisers include: showing their value compared with robo-advisers and peer advisers, improving their value by using the most efficient software, prioritising their time well, and meeting their clients’ ever-shifting preferences. All these various challenges come back to the core principle of value and, specifically, demonstrating that value to clients.

One reason advisers struggle to communicate this value could be the discrepancies between what investors actually value and what financial advisers think investors value. In our research, we found that these two groups’ perspectives don’t always align.

Here, we discuss what contributes to this gap and how advisers can help bridge it.

What we can learn from the gaps

For this research, we asked individual investors to rank a set of common advisor attributes—such as “Helps me reach my financial goals” and “Understands me and my unique needs”—in order of importance. We also gave the list to advisers and asked them to rank the attributes in the order they thought investors found most valuable.

When we compared the average rankings of both groups, there were quite a few crucial disagreements. However, many of them can be mitigated through proper communication.

How to help clients understand true financial advisor value

Because of these discrepancies, it’s important for investors and advisers to effectively communicate and ensure that they’re on the same page about the client’s goals.

Here are three key topics advisers should broach with clients to help communicate their unique perspective and value.

Step 1: Demonstrate the importance of personalised goals-based planning. Implementing a goals-based strategy can increase a client’s wealth by more than 15%. This may come as no surprise to financial professionals, given the known benefits of personalised advice, but individual investors may have a different perspective. Our research found that although financial advisors think that personalisation is very important for their clients, individual investors ranked it much lower on their list. Given the effectiveness of personalized advice, advisers should not take for granted that investors are committed to a goals-based strategy. Rather, they can provide a high-level overview of a goals-based strategy’s effectiveness to help investors understand the impact it can have on their overall wealth.

Step 2: Introduce clients to the world of behavioural coaching. The modern adviser is now also a behavioural coach: Someone who helps their clients weather market volatility and stay on track with their financial plan. This service is both unique to in-person advisors and extremely effective at improving their clients’ performance. But unfortunately, it’s another attribute investors take for granted—in fact, they ranked it as the least valuable attribute. To help more investors understand the value of behavioural coaching, advisers can start introducing clients to the field of behavioural science. You can get started with the resources and exercises we created for advisors to use with clients and display the importance of behavioural finance in investing.

Step 3: De-emphasise maximising returns. The role of an adviser has evolved substantially since the time when investors only went to advisors for stock tips or investment strategies. Some clients, though, may be stuck in the past. In our research, investors continued to rank “Helps me maximise returns” high on their list. To help clear up this misconception and demonstrate deeper value, advisers can provide examples where chasing returns can hurt an investor’s progress toward their goals. For example, a client that is three years from retirement should focus on maintaining their wealth, not taking on risk to increase return.

Showing the breadth of financial adviser value

Our research points to one overall finding: Financial adviser value is currently misunderstood. The role of an adviser is no longer just to be an investment expert; it’s also to serve as a behavioural coach, financial counsellor, budgeting master, and more.

Advisers wear many hats, and the evidence suggests that investors are having trouble recognising all the ways an adviser can help them with their finances. Having these conversations with clients may help.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

Market turmoil is an opportunity to assess your own practise

by Sheryl Rowling

The stock market’s unpredictable response to coronavirus is an opportunity for advisers.

Not in the traditional way of “buy when there is blood in the streets” – though that could still be useful.

Instead, it’s an opportunity to test your ability as an adviser to assess your clients’ risk tolerances, and whether their risk profiles and investment strategies are aligned to meet their goals. In fact, it’s a good time to revisit the question of how we as advisers determine how much risk a client can, and should, be taking.

It’s also a time to assess how effective your client communications and coaching has been. How are your clients responding to the market turmoil? If your phones are lighting up and your email inbox is clogged, you may want to ask some questions about your process.

That’s because managing portfolios for clients is not simply a calculation exercise. It involves working with clients through the market’s ups and downs–coaching, communicating, reassuring. To properly invest on behalf of clients, we advisers must consider a variety of factors in addition to the client’s personal feelings on risk.

And there’s nothing like a double-digit plunge in stocks to reveal if you have overestimated how strong a stomach a client has.

The more sophisticated approach to risk tolerance

This question starts at the beginning, when a client first comes on board.

For the most part, advisers will assign a risk-tolerance questionnaire to new clients prior to investing. The risk-tolerance questionnaire will generate a score, and then the score is matched to an appropriate corresponding portfolio allocation. This methodology is simple and easily documented for compliance purposes, but it is only one piece of the puzzle. A more sophisticated approach allows advisers to look at how a client’s risk-tolerance questionnaire relates to his or her capacity to take on risk, and how that capacity informs long-term goals.

That’s because no matter how risk-tolerant the client is, consideration must be given to the capacity to take on risk from the perspective of the client’s ability to reach goals notwithstanding market volatility.

For example, an extremely wealthy client will likely have more risk capacity than a working couple whose only investments are their superannuation. Indicators of greater risk capacity include stable employment, outside investments (like real estate), younger age, good health, potential inheritances, and so on. Indicators of lower risk capacity include unstable employment history, no outside investments, older age, poor health, dependent parents, and so on.

Coaching and communication

A more sophisticated approach to risk tolerance also requires advisers to be pre-emptive when an actual or potential market event could cause clients emotional distress. As we are seeing now, anxiety as the coronavirus continues to spread is causing many investors to panic.

When you truly understand every facet of your client’s risk tolerance, goals, and investment strategy, it is easy to reach out pre-emptively to prevent emotional decisions and reinforce the “stay the course” approach.

Both downside and upside risk can be big emotional triggers for clients. When it comes to their life savings, people are understandably nervous and upset when their portfolio shows losses or doesn’t reflect the amount of growth they think it should.

I sometimes say that my greatest value to clients is keeping them from making these kinds of emotional decisions that will hamper their ability to meet their goals. This means I need to continually coach and reinforce the “stay the course” mantra.

Since each client is different–and can react differently depending on the situation—I recommend ongoing, multifaceted communication. In my firm, we educate clients beginning with the introductory meeting and every annual review. We offer webinars, present seminars, send newsletters, include information in quarterly letters, and send timely emails during periods of market shifts.

Being proactive is extremely important in helping clients stay the course.

This time around, even before things got really ugly in the markets, we sent an email to clients on Feb. 20, 2020, with the subject being “The Coronavirus & Your Portfolio.”

This is how we started the email: “As I write this, the market is at an all-time high. Although this is good news, it always prompts the question: When will everything drop?”

Of course, we didn’t really know what was about to happen! But we walked clients through previous episodes of epidemics and their market impacts. The goal was to show our clients that we were paying attention and we have done the work to back up our recommendations.

When you reach out early and often, keeping clients informed and reminding them why their investment strategy works, they are much less likely to panic and let their emotions take charge.

We followed up with an email on Feb. 27 with the subject line “The Sky is Falling! (Stay the Course, Version XXXIII).”

Throughout this coronavirus market decline, we have had only three clients reaching out with concerns. We were able to talk to each of them and provide reassurance. And the other 250-plus clients? We didn’t hear from 90% of them. The remaining 10% responded by thanking us for watching out for them.

Control what you can

A market drop like the one we are experiencing now can be a great opportunity for an adviser to remind clients of the work you are doing behind the scenes. That’s because staying the course does not mean “do nothing.” It means adjust as needed.

And when you are able make lemonade out of lemons, let your clients know! They will remember the next time and will panic less.

Conclusion

The market is unpredictable. There is no way to know what it will do in the future or to control it. Our clients know this, even if their emotions sometimes get the best of them.

As advisers, it is our job to take all of this into consideration when initially creating an investment strategy. However, at least as important is the client’s ability to stick with the strategy through the ups and downs of the market. So, it is equally important to continually assess risk tolerance through coaching and frequent communication.

Sheryl Rowling, CPA, is head of rebalancing solutions with Morningstar and principal of Rowling & Associates, an investment advisory firm. She is a part-time columnist and consultant on adviser-focused products for Morningstar, and she continues to actively run her advisory business, from which Morningstar acquired the Total Rebalance Expert software platform in 2015. The opinions expressed in her work are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

When We Buy Stocks… And Why (est. read time: 5 min)

“Whether we’re talking about socks or stocks, I like buying quality merchandise when it is marked down.” [1]

— Warren Buffett

Buy Low & Sell High, The Right Way

Let’s say you own a great business today and the price falls by 40% tomorrow. Should you buy more of it? All else being equal, you would be foolish not to buy more as long as your conviction in the intrinsic value of the business remains intact. Yet, the process of buying high-quality businesses at low prices is beset with behavioural challenges and something every investor must consider carefully.

Key Takeaways

- For stock investors, every buying decision requires fresh perspective, regardless of whether the stock is trading near its low or high.

- Investors need to be careful when buying stocks in certain situations. We believe structural change, rapid disruption, leverage, and poor capital allocation are all primary concerns.

- Buying into weakness often makes sense, but it is not easy and can sometimes be the wrong thing to do.

- In a portfolio context, we strive to adhere to a structured process to maximize the probability of making good decisions.

Identifying Risks When Buying Stocks

Some of the key risks to stock investors tend to cluster around the following situations:

- Industries undergoing structural change. This can evolve via comprehendible means (an ageing population or industry in structural decline) or via rapid disruption that is harder to distinguish (wiped out via technological advancements).

- The erosion of an individual company’s economic moat. A company without a durable competitive edge may benefit from a fad or it may temporarily benefit from a first-mover advantage, but will ultimately succumb to another company with a stronger competitive positioning.

- Leveraged businesses that succumb to debt constraints. Prominently, if an investment falls in price, the debt can suffocate the capital, creating the conditions for a perfectly good business to be a value trap.

- Businesses with poor capital allocation. For example, undertaking a monumental capital expenditure program when there isn’t the cashflow to support it, destroying the value of the business. Overpaying for an acquisition, especially without a strategic fit, or not reinvesting enough back into the business (research and development) could be other examples.

The other, which is likely to have relevance today, is when assets are still expensive. This may not fit the classic definition of a value trap, but an asset going from extremely expensive to moderately expensive is unlikely to make a good investment, even if the price has fallen meaningfully.

Lessons from a Classic Collapse

Some companies can appear strong on face value but tumble into structural decline. Take Kodak for example, where many investors in the 1990’s never anticipated the progression of digital cameras, nor that Kodak would be left behind in that progression. Buying in the dips would have been a terrible idea for most investors, as you would have continually bid up this exposure only to find it halve, halve and halve again.

Underpinning the above risks, a key challenge is that early and wrong can sometimes be indistinguishable in the initial stages of an investment. An investor who is early would likely prefer to increase their exposure as the probability of a turnaround increases (much like a poker player should). However, if that investment becomes wrong (a value trap), they should consider accepting their losses and moving on. It is entirely possible to be both early and wrong if the nature of the asset changes over time.

This is also a warning that cheap assets can get even cheaper, so it isn’t enough to simply buy cheap companies. We need to ensure the quality of their cashflows are sound and that they have durable advantages that allow for the benefits of compounding. For example, if a poor-quality investment falls by 20%, but could fall a further 30%, 40% or 50%, we likely want to avoid going all in.

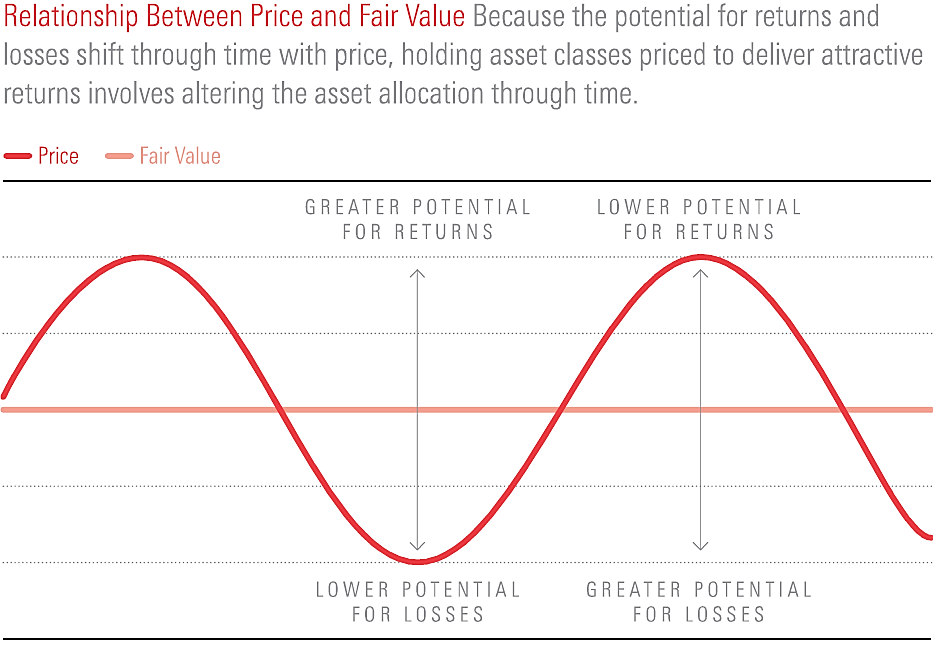

Exhibit 1 The relationship between price and fair value is the principle that guides valuation-driven investing. However, it does open potential issues regarding value traps.

In principle, if we want to buy high-quality businesses at prices below their intrinsic value, we must conform to the idea that we might be early to the party. After all, you are likely buying the investment today because it is unloved and no one else wants it (yet). By undertaking this exercise, there are no guarantees someone will want it next week, month or even year. Hence the reason value investors often cherish the word ‘patience’.

Our Process When Buying Stocks