7 Faux Pas for Financial Advisers To Avoid

Time and again, research shows the personal relationship between a client and their adviser is paramount to both parties’ success. Without a strong personal relationship, advisors cannot provide the customized, high-quality level of advice that clients are looking for nowadays. Because of this, clients may disengage with their advisor or outright fire them if they experience a lack of personal relationship along with lackluster advice.

In our latest research, we investigated which adviser behaviours contribute to investor disengagement. Moreover, we dove into how investor disengagement presents itself in the adviser-client relationship.

Death by a Thousand Cuts

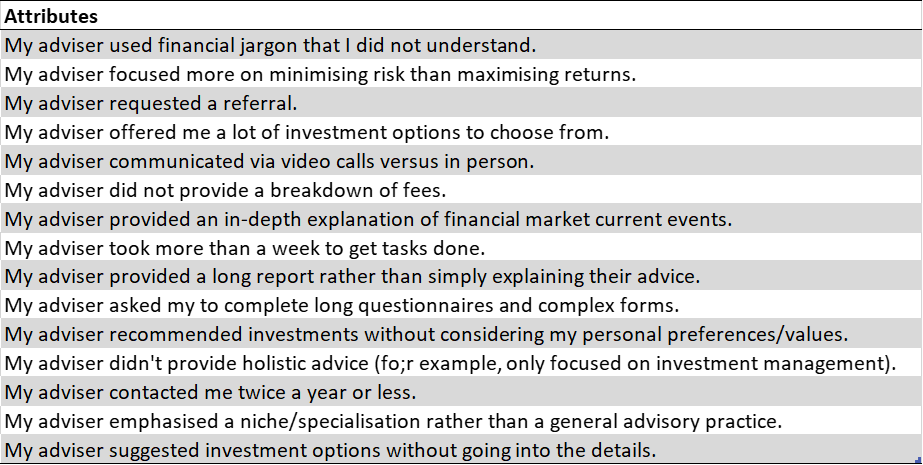

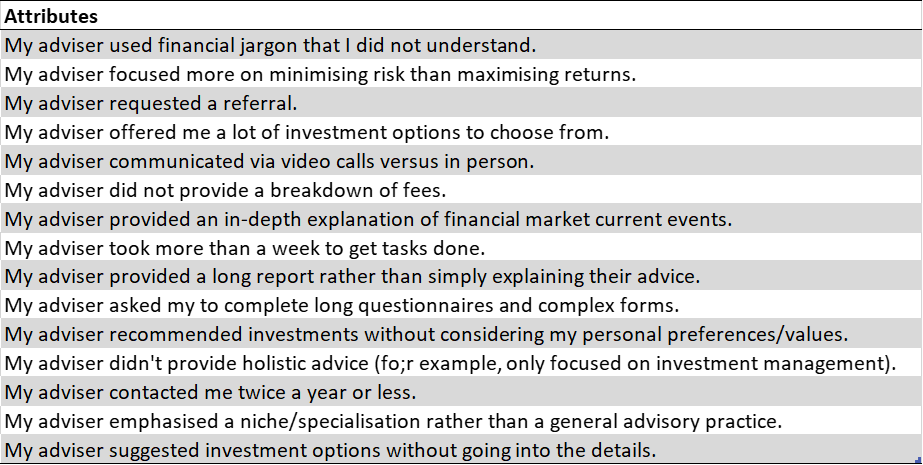

We started our research by collecting common adviser behaviours. We then asked adviser clients to rate how frequently they experienced each behaviour. For those they reported experiencing, we asked participants to rate their emotional response to the behaviour (on a scale from “I really disliked it” to “I really liked it,” with a neutral midpoint). We then asked participants how each behaviour affected their relationship with their adviser across four dimensions: their trust in their adviser, their decision to collaborate with their adviser, their decision to allocate assets for management, and their decision to recommend their adviser to others.

Which Common Adviser Behaviours Do Clients Dislike Most?

We found seven actions that clients reported disliking (in order from most to least disliked):

- Did not provide a breakdown of fees.

- Took more than a week for tasks.

- Used financial jargon.

- Recommended investments without considering values.

- Suggested investment options without going into details.

- Asked me to complete long forms.

- Did not provide holistic advice.

For the rest of the actions in the survey, clients reported either neutral or positive feelings (see paper for full results). To understand the impact of these disliked behaviours, we created a composite score of the four dimensions and then identified the relationship between the score and each disliked behaviour. We found that how much a client disliked an action had a moderate, negative impact on their relationship with their adviser. In other words, an investor experiencing a disliked behaviour was discouraged from trusting and recommending the adviser, as well as encouraged to invest less with and to stop working with the adviser.

Faux Pas No More: Being Conscious of Disliked Behaviours

Some of the adviser behaviours we investigated in our research may seem harmless on the surface but can lead to disastrous wounds over time. It’s all too easy to wave off these results, with the claim that you (as a financial adviser) don’t do these things to your clients. Other advisers use financial jargon that leave clients confused or speed past investment explanations. Not you, of course. Unfortunately, we find more than half of the clients experienced each of these behaviours with their own advisers—making these behaviours a lot more common than any adviser should be comfortable with.

To help advisers make sure they aren’t one of the culprits, we created a two-step takeaway that’s accessible in the full white paper. The first step is a checklist that advisers can use before and during a conversation with a client, so they can reflect and address the top five disliked behaviours we found in our research. Step two is a follow-up survey template that advisers can send to clients after a meeting. The survey subtlety asks the client if they experienced any of the top five disliked behaviours during their meeting with their adviser. Compared with being face-to-face, the online format of the survey may encourage honest feedback; instead of being put on the spot, clients have time to reflect on the meeting and provide comprehensive feedback.

Together, this two-step takeaway can help advisers ensure they are not accidentally tearing down the relationships they meant to develop.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

Investment Insights: Bond yields and the Mideast conflict

Bonds are a core part of most investor toolkits. They come in different shapes and sizes, but have historically offered two strong propositions:

- Safer bonds, such as Australia and US Government bonds, can act as a ballast against stock market volatility, balancing the risk/return pendulum.

- Bonds usually offer positive returns above inflation, typically beating cash over the long run.

This is not the recent experience. With the sudden rise in interest rates and surprisingly strong employment numbers, we’ve seen a big move up in global bond yields. This has left many investors with bond allocations in the red again for 2023, following declines in 2022.

The narrative gets more confused in the wake of the attack on Israel and Israel’s response. It’s not unthinkable that an adviser or client may wonder whether we can still count on Government bonds as a safe haven in times of geopolitical crisis. (By “safe haven” we mean that in particular U.S. Government bonds are one of the few asset classes investors turn to broad market selloffs.)

So, do bonds still deserve a place in a portfolio? Should investors maintain their long-standing rationale for mixing bonds and stocks together? And what can we expect from bonds, given the tragic developments in the Middle East? While it may be difficult to swallow, there are reasons for optimism for the future of fixed-income returns.

Are bonds a safe haven in the midst of the recent conflict in the Middle East?

Given the sudden and continuing tragic situation in Israel and Gaza, let’s tackle the “safe haven” status first. In recent months, the safe haven status of U.S. Government bonds has been a topic of debate. With concerns about the U.S. government’s huge deficits and the Fed’s higher-for-longer narrative (which could mean the U.S. needs to pay more to cover its debt payments) some have speculated on whether U.S. Government bonds’ safe haven status is intact.

We believe it depends on the risk in question. If equities or credit decline because of concerns surrounding interest rates, then Government bonds may not provide the ballast investors would like. That’s indeed what we saw in 2022.

However, in the case of geopolitical conflict, the focus is on risk aversion generally. In this case, relative safety in an unstable world matters most, so we expect Government bonds to act as a store of value, particularly in the U.S. but also in highly rated countries like Australia.

The trouble comes from the confluence of events, as these geopolitical risks occur at the same time as rate rises. In those instances, our preference is for the shorter end of the yield curve. This generally means Government bonds with a maturity date of less than five years, which have yields in excess of 5%, in the U.S. with the backing of the U.S. government and limited interest rate risk.

Do we still think bonds are a good investment?

Looking forward, our outlook for fixed-income returns remains optimistic. Yields are resetting at higher levels, while prices are declining, creating attractive opportunities in fixed income from a valuation perspective.

Particularly, areas like short-term Government bonds, boasting yields of 5% or higher in the U.S., present an opportunity for investors to bolster their portfolios with substantial income without exposing themselves to excessive duration risk (a measure of interest rate risk).

Conversely, in the U.S. the longer-term debt market faces persistent pressure due to expectations of prolonged Federal Reserve policy and the enduring strength of the economy. With the sell-off in long-term global Government bonds, we are cautiously optimistic about the better prospects for higher returns and income, though we still advise investors to carefully consider their overall exposure to duration.

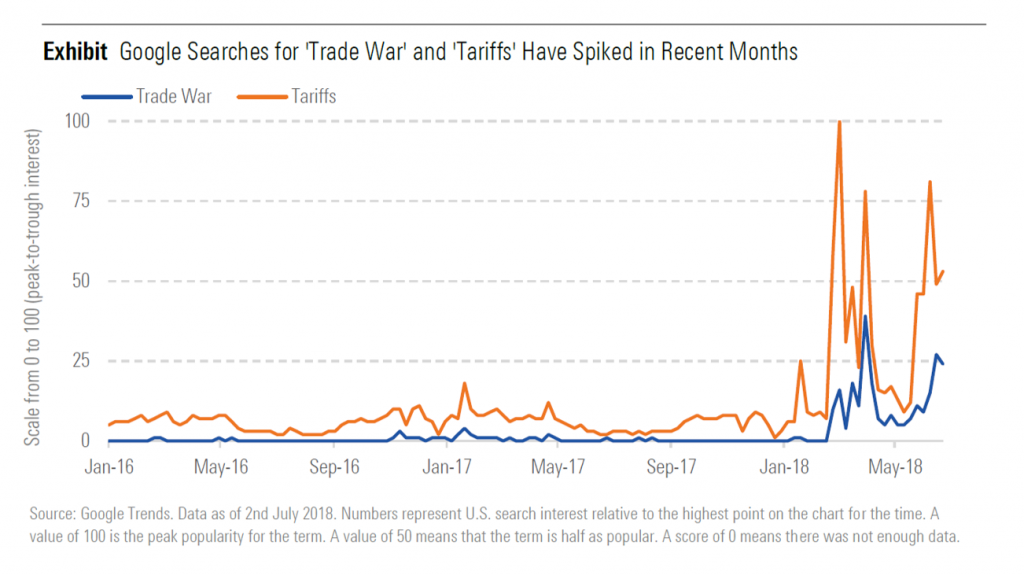

Why are Treasury yields still rising?

Reflecting on the beginning of the year, the financial landscape and consensus projections unanimously painted an optimistic picture on inflation moderating, coupled with a pessimistic view of developed economies in the process of slowing down due to the assertive measures taken by the central banks. Subsequently, we have witnessed a rollercoaster of developments that have notably yielded a remarkably resilient U.S. economy, seemingly impervious to the policy manoeuvres of the Fed. Furthermore, certain aspects of the global economy suggest that attaining the central banks’ inflation targets may require more time than initially envisaged.

First and foremost, labour markets in Australia and the US remain the driving force behind a stronger consumer than expected, despite a significant increase in interest rates over the past 18 months. A lower-than-average supply of workers, coupled with persistent demand for goods and but particularly services, has maintained hiring at a pace that surpasses typical expectations in a rising interest rate environment. In the US, fiscal policy, characterised by increased spending and widening budget deficits, is acting as a stimulant for the economy, contrary to the Fed’s objectives in its battle against inflation.

Are central banks’ “higher for longer” messages the main catalyst?

Taken together, this backdrop has fostered the notion that interest rates will remain elevated for an extended duration. Consequently, long-term bond yields have surged significantly within just a few months, as markets brace themselves for this scenario—an outcome that was not accounted for just half a year ago. As long as the labour market retains its resilience in the face of monetary policy actions, fiscal policy remains accommodative, and overall demand remains on a steady course, the Federal Reserve and the RBA lack a compelling motive to shift away from its hawkish stance. An untimely shift toward a more accommodating position poses the risk of inflation rekindling, reminiscent of the Volcker era in the 1980s.

To reiterate, the concept of enduring higher interest rates was not factored into market forecasts earlier this year. Now, we are witnessing markets adapt to this new reality in real-time, as it becomes evident that the economies have so far been more resilient than anticipated.

Any new risks we need to think about? What are the consequences of higher rates?

As financial markets continue to absorb the implications of prolonged elevated interest rates, the practical consequences in the medium term may face challenges. In the U.S. we are witnessing the impact on the housing market, where we observe declining prices and subdued demand while in Australia the housing market has bounced back from steep losses. Furthermore, consumers who had previously been buoyed by stimulus measures during the Covid era have now depleted their surplus savings, which had been a driving force behind the remarkable demand surge in 2020 and 2021. With diminished savings and higher interest rates affecting credit cards and loans, as well as increased prices for everyday essentials, the risk of reduced consumption looms large.

If demand erosion becomes widespread, it could jeopardise the revenue and cash flows of companies across the board. This, in turn, could lead to a reversal in hiring trends or even sustained job cuts across various sectors of the economy. These same businesses are also susceptible to higher debt costs when they need to refinance or raise capital. Many of these companies have outstanding low fixed-rate debt issued during 2020 and 2021. However, if the central banks maintain their commitment to prolonged higher rates, companies will be compelled to refinance in a substantially higher interest rate environment, adding pressure to their ability to manage their debt.

What’s the likely impact on the economy?

In summary, elevated interest rates have a tightening effect on the overall economy. Some repercussions manifest suddenly, as seen in the housing market, while others have a delayed impact and take time to materialise, such as in labour markets. There is reason to believe that the RBA and Federal Reserve may stick to a higher-for-longer policy, and history suggests that recessions (hard landings) occur more frequently than smooth economic transitions (soft landings). However, predicting when or if such an event will occur remains challenging. Therefore, it is advisable to construct investment portfolios with a range of potential outcomes in mind, avoiding undue bias towards a single scenario.

Do Government bonds still offer the same diversification?

As a core holding among many investors, owning longer-term Government bonds usually offers a twofold benefit:

- First, it mitigates the opportunity cost of remaining invested in short-term debt. In the event of a Fed policy reversal and interest rate cuts, short-term debt could experience a sharp decline in yields, forcing investors to refinance at significantly lower rates. Maintaining exposure to long-term bonds secures higher yields both today and for an extended period, thereby reducing opportunity costs.

- Second, long-term Government bonds have historically served as effective diversifiers in the face of credit and equity risks during market downturns.

While we acknowledge the possibility of continued economic resilience, the potential for a conventional downturn should not be discounted. In such a scenario, long-term bond exposure could still offer a hedge against riskier segments of your investment portfolio. Nevertheless, it’s important to note that during this cycle, the diversification benefits of long-term Government bonds have been less pronounced, primarily due to a higher inflation environment. If inflation proves to be more persistent than anticipated, the traditional negative correlation between long-term Government bonds and equities may not be as robust.

Does the “inverted yield curve” mean anything in today’s context?

The current shape of the US yield curve could pose a challenge for long-term Government bonds potentially mitigating equity risk. Our studies have demonstrated that in instances of an inverted yield curve, long-term Government bonds have shown diminished ability to shield against declines in equity markets. Conversely, in situations where the curve steepens (with long-term interest rates surpassing short-term rates), long-term debt has exhibited the ability to garner substantial returns amid periods of declining equity markets.

What do we think of corporate bonds in this environment?

While corporate bonds still have a place, we find credit to be relatively overpriced. Whether examining investment-grade or high-yield debt, we are unable to justify an overweight position at present. The spreads investors receive for holding this debt are currently at or slightly below long-term averages. In other words, taking on risky debt like high-yield bonds offers limited yield advantages relative to risk-free alternatives. Additionally, given the heightened likelihood of a recession, relatively speaking, we are uncomfortable with current valuations.

In the near term, further volatility is possible, so managing risk is important. But Government bonds offer positive forward-looking prospects after inflation, and we continue to see merit in these holdings.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

Even Advisers Aren’t Immune to Overconfidence Bias

By Samantha Lamas, Behavioural Researcher

We are all constantly making predictions about our lives, both professionally and personally. For financial professionals, predictions can have a drastic impact on a client’s financial success. This tends to show its prevalence during the so-called outlook season, when industry figures share their forecasts for the year ahead.

The overconfidence bias is just one of the many biases we face, but it can be especially difficult to accept. No one likes to hear that they are overconfident, let alone someone who has spent years building up their expertise. But when professionals open up to the idea that overconfidence bias can impact their business, it may help them better serve their clients and avoid the well-known traps that trip people up as they grapple with persistent uncertainty.

Defining Overconfidence Bias

Many people are familiar with a classic study of overconfidence that finds that the vast majority of people think they are above average in terms of their driving skills, but overconfidence also shows up in many other aspects of life.

There are at least three types of overconfidence, according to Moore and Healy:

- Overestimation—People think they are more skillful than they actually are.

- The better-than-average effect—People think they are superior to most others in a reference group.

- Miscalibration—People are more confident in their judgments and predictions than they should be given their accuracy.

Although all forms of overconfidence are pertinent for financial professionals, miscalibration can be especially harmful. Financial professionals are often asked to predict the future—What is this fund going to do next? What about interest rates or the economy?—and, usually, a lot is riding on those judgments and predictions. Given the stakes, it is important for professionals to not only make accurate judgments but also to understand the justifiable degrees of confidence in their judgments. Unfortunately, research shows that many financial professionals, like experts from many fields, suffer from varying levels of miscalibration and overconfidence.

Among the dark clouds, there is a silver lining in making appropriate and responsible predictions for a living. Meteorology is one profession identified as being by and large well-calibrated in this regard. The success of meteorologists doesn’t imply they are omniscient or perfectly accurate; instead, it means that, for example, when a weather forecaster says she is 70% sure of the weather tomorrow, there is actually a 70% chance she is right. Good calibration is about properly understanding the limits of what one knows and being able to consistently identify when high confidence is warranted and, conversely, when humility is necessary.

Predicting the Weather vs. Predicting the Markets

Just like financial professionals, meteorologists undergo rigorous training to prepare for their role. However, meteorologists face a very different environment compared with financial professionals. When it comes to predicting the weather, past data can be reliable (to some extent) in predicting the future, and quick feedback is available.

The financial markets, on the other hand, aren’t as easily predictable nor as easy to learn. When it comes to investments, past performance does not necessarily predict future performance. Many forecasts take long time spans to unfold, some forecasts can influence market behaviors, and massive price swings can come from the most unexpected of places (remember GameStop?).

Regardless of the environment, there are still adaptable techniques financial professionals can use to combat overconfidence bias.

How to Combat Overconfidence Bias

Here are six steps you can take to be better calibrated and avoid overconfidence bias:

1) Establish deep domain knowledge.

Any good prediction must start with the right information and knowing what to pay attention to (and just as important, what information to ignore).

2) Adopt the right mindset.

The best forecasters view their “beliefs as hypotheses to be tested, not treasures to be guarded.” Adopting a how-might-I-be-wrong mindset can act as a buffer against overconfidence. It may be helpful to engage in a “what if” exercise where you consider what evidence it would take for you to change your mind and make a substantially different forecast.

3) Think in ranges (and bets): Define confidence level and range of outcomes.

Some predictions are amenable to using ranges. For example, consider the phrase “I am 90% confident that the price of XYZ will be between $18 to $21 per share at the end of the second quarter.” Notice how this prediction avoids fuzzy phrases like “strong possibility” or “real chance” and the forecaster pins herself to being 90% sure and using a range of values to express her confidence—also known as a confidence level. If she made 100 of these kinds of “90% sure” predictions, we would expect her to be right (within range) 90% of the time. Using a confidence level to express confidence in a prediction enables it to be recorded to establish a track record that validates one’s accuracy.

This format also makes it easier to “think in bets.” If a person is 90% sure of something, they should be willing (if not eager) to take a 1:8 payoff bet (they put $8 on the table—if they are right and the prediction is in range, then they get their $8 back plus earn a dollar; if they are wrong, then they lose their $8). If they are well-calibrated, they’ll make money in the long run. Now imagine you encounter a person who says he is 90% sure of something but would only be willing to take a 1:2 payoff bet. Something doesn’t add up. By no means are we advocating rampant gambling, but there is power in participating in some low-stakes and relatively safe risks to help people discover how confident they really are and reconcile that with the level of confidence they portray.

4) Aim for precision.

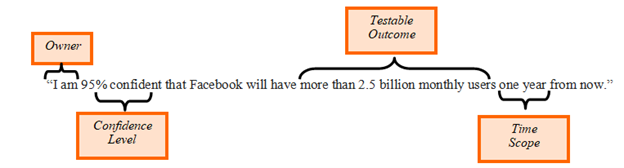

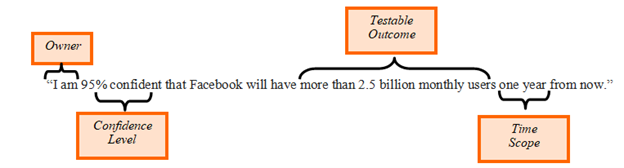

Precise and clear statements can be tested. When making a prediction, be sure it has the four key elements:

- Owner

- Confidence level

- Quantitative outcome

- Time scope

For example, the statement below states who is making the prediction, the exact level of subjective confidence, a testable count of monthly users (which could eventually be determined as right or wrong), and a time scope. This is a testable prediction and can be a useful statement.

5) Keep quantified and dated records.

Consider writing down a testable prediction, the time frame, and the confidence levels you assign to each possible outcome (you can also use ranges if that works better for the type of forecast). Try to also include some notes of how you reached that conclusion—what process did you follow, what sources did you include in your research, who did you consult for contradictory opinions, what evidence would it take to change your mind, and so on.

After the time scope and the outcomes are known, go back and record what happened, alongside your original prediction. Over time, you’ll be able to see the accuracy of your forecasting abilities and the tactics/process that led to well-calibrated predictions.

6) Surround yourself with diverse perspectives.

Because of our biases, we tend to seek out and pay more attention to information or opinions that support our own. We may be inadvertently discounting a whole side of information because it doesn’t match what we already think. To avoid this mental trap, we must surround ourselves with diverse perspectives and opinions. Moreover, we must foster an environment where constructive criticism and deferring beliefs are encouraged and taken seriously. There’s no room for egos here.

Professional Demands and Good Calibration

Individual investors generally expect their advisors to be confident—few clients would want to hear their advisor say something like, “I genuinely have no idea what the returns will be for this fund in the next six months …” But it is worth being mindful that there is a difference between exuding professional confidence and being overconfident. Financial professionals can establish justifiable confidence about long-term investing strategies and well-established principles from investing research. They can also redirect their client’s attention away from what is likely unknowable (for example, how will the price of this exchange-traded fund move in the next month?) toward things that are better known (for example, which asset class can expect more volatility in the next 10 years?). Fortunately, successful investing does not require being able to predict the future.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

Are your clients preparing for retirement? Here’s what they should watch out for

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. In this case, preparing your clients for common sticking points as the get ready to retire can save both stress and money.

Decades spent in accumulation mode can make even the most financially savvy retirees ill-equipped to enter this new phase of life. Christine Benz, Morningstar’s Director of Personal Finance, has seen it happen. “Even retirees who are seasoned investors will tell you that transitioning from accumulating to spending from their portfolios is a challenge,” she says. Not to mention the obvious behavioural challenges that come with a dramatic change: “There are also psychological hurdles to jump over: After years of saving, transitioning into drawdown mode can feel a little bit scary.”

So how do you, the adviser, ensure your clients are in a good position to forge ahead in their retired life? Here are four key points to check off with your client.

We’re living longer

We’re living longer

As time ticks on, life expectancies are growing longer. According to Philip Petursson, Chief Investment Strategist and Head of Capital Markets research at Manulife Investment Management, research by the World Economic Forum has found a person born in 1947 during the post-war baby boomer generation would have an average life expectancy of 85 years. If you were born 30 years later, that expectancy jumps almost a decade – to 94 years.

Longevity risk is arguably the dominant risk for today’s retirees. David Blanchett, Morningstar Investment Management’s Head of Retirement Research, points out in his report ‘The Retirement Mirage’:

“Choosing when to retire is one of the single most important financial decisions we make in our lives. Knowing when we plan to retire helps determine how much money we need to save and our standard of living in the meantime.”

“Unfortunately, our retirement plans are often wrong. People retire earlier than expected for a variety of reasons—including health issues and job changes—but the impact can be severe.”

This is exacerbated if your client retires earlier, lives longer, and increasingly, was born later. Petursson notes that someone born in 1947 would need roughly 50 per cent more capital than a person born in the previous generation, and someone born in 1977, would require an extra 30%.

With the longevity risk comes a shortfall risk: the possibility of outliving one’s savings. In fact, to cover for the longevity and shortfall risks, and considering that 94 years is an average life expectancy, a retirement plan should be developed with the expectation of the client living to 100. “That’s what I calculate for,” says Michelle Munro, tax and retirement expert at Fidelity Investments.

A recent survey of 1,929 respondents by Fidelity (Retirement 20/20) shows that only 17 per cent plan that far out. The largest cohort (53 per cent) plans between 85 and 95 years of age, and 28 per cent plans between 70 and 80 years of age.

“Our findings suggest that given this uncertainty around retirement age, some investors may need double their current savings to achieve their retirement targets. A person’s retirement age is simply too unpredictable, and we must plan accordingly to help avoid negative surprises,” Blanchett says.

The health curveball

The health curveball

The other major blind spot of retirees is health care and assisted-living costs.

“You often read about all the money you’ll save when you’re no longer working–on dry-cleaning, commuting, lunches out, and not having to save so much for retirement anymore, says Benz.

“Given that cavalcade of savings, it’s not surprising that so many retirees fall back on the conventional wisdom that they’ll only need to replace 80 per cent of their income during their working years when they actually retire.

“In reality, that 80 per cent rule is at best a rule of thumb; some retirees actually spend more than they did while they were working, while others spend much less. (Healthcare costs are one of the biggest wild cards).”

One area where expenses can explode: intensive care for the last period of one’s life, which could range from a few months, to a few years. “That is a huge expenditure,” highlights Munro, adding that the last third part of one’s life will probably not be a beach party.”

From 1994 to 2015, life expectancy at birth of males rose from 75 to 80 years, indicates a 2018 StatCan report, but health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE) went from 65 to 69 years. For women, life expectancy at birth increased from 81 to 84, years, and HALE, from 68 to 70.5 years. Men have to plan with the potential of about 11 years of health complaints; women, with 12 years.

Among the six health attributes of mobility, pain, sensory, dexterity, emotion and cognition, mobility stands out as the more important source of diminished health for males, while for females, it is mobility and pain.

Asset allocation ‘rules’

Asset allocation ‘rules’

Many people talk about a simple rule of thumb: 100 minus Age = Equity. Put another way, if you’re clients are 70, 70 per cent of their portfolio should be in bonds.

But that is not practical anymore. “Historically low interest rates cause revenue on ‘safe’ investment grade bonds to be insufficient to generate revenue for many retirees,” says Petursson.

“Today, our capital in retirement still needs to generate a return, yet it’s harder and harder to generate a return with interest rates. The challenge for retirees is to find asset categories that will still generate return while not inordinately increasing risk.”

To mitigate that risk, it appears that coming retirees plan to continue working beyond retirement. Blanchett calls delaying retirement a ‘silver bullet’. “You’ve got one more year to save, one more year for your assets to grow, one less year to plan for in retirement. So, it’s really, really good,” he says.

The planning blind spot

The planning blind spot

The Fidelity survey clearly points to a potential area of hardship: neglecting to devise a retirement plan. Asked about their level of financial preparedness for retirement, 94 per cent of retirees who have a plan claim that they feel prepared, but only 72 per cent of those without a plan claim as much. Among pre-retirees, the difference is sharper: 78 per cent of those with a plan say that they feel prepared, but only 44 per cent without a plan say so.

Munro insists that such planning should preferably be carried out with a professional – that’s where you come in. But your clients shouldn’t limit their plans to financials only. Key areas of retirement to consider are one’s social and emotional health. It’s now an established fact that people who have strong networks of relatives and friends age better. Let’s drink to that! But not too much…

For more information about our retirement tools and portfolios, and how we can help you support your clients as they transition to retirement, contact your Adviser Solutions Manager.

This article has been re-written for an adviser audience. You can read the original, by Yan Barcelo, here.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

Three strategies for your clients’ post-pandemic spending and saving plans

by Samantha Lamas

The pandemic forced us all to form new habits in every aspect of our lives, including how we spend our money. Instead of grabbing lunch with friends or planning our next vacation, many of us stayed home and experimented with sourdough bread recipes. Environmental restrictions, while keeping us safe, also inadvertently prevented many of us from excess spending.

As many locations begin easing restrictions, many predict a boom in consumer spending. For those who are enjoying their healthy savings accounts, there’s a downside to partaking in that boom.

To help your clients stick to their saving goals, guiding them through a reflection process may be key to prolonging the good habits they’ve adopted.

Creating a new habit depends on a few factors: the difficulty of the desired behaviour, the context or environment of the decision, and the incentive associated with the behaviour. Many times, people struggle to create a new habit because they disregard the importance of their environment.

For example, if your goal is to lose weight, one of the most beneficial steps you can take is to get rid of any temptations in your kitchen. During the pandemic, restrictions acted as that environmental fix, where individuals were shielded from the temptations of overspending in in-person settings. However, this strong-armed fix may soon be coming to an end.

For clients who would like to continue building up their savings accounts, now is the time to help them prepare for the loosening of restrictions and the impact that may have on their financial decisions.

Identify

Start off by helping clients identify the good behaviours they’ve adopted over the past year.

- Did they start setting aside money for saving right when they got their paycheck?

- Did they cook at home more often?

- Have they gotten into the habit of saving up for big purchases or vacations versus putting things on a credit card?

Ask clients to write down the good habits they would like to stick to in the future and why. What financial goal will they get closer to by sticking to this habit? The practice of writing out a behaviour and reconnecting it to a personal financial goal can act as a precommitment device–a “contract” between your clients and their future selves that they can look back on when the habit begins to falter.

Prepare

It’s important to acknowledge that our current environment has helped us stick to our new spending and saving habits. As social distancing restrictions begin to loosen, we must brace ourselves for the times when our new habits may be tested. For example, socializing may start to become more common, along with the expenses that come with it.

Under these circumstances, it may be difficult for clients to keep certain habits, like spending less on eating out or entertainment. To prepare for this new environment, help your clients identify the needs they are trying to satisfy with certain behaviours and come up with a new strategy to meet those needs. For example, spending money on expensive dinners may have more to do with the need for socializing versus the meal itself. Help your clients find a budget-friendly strategy for meeting this need, such as inviting friends over for a home-cooked meal instead.

Block

No matter how much we prepare, our newfound habits may still falter under pressure. As a solution, work with your client to create barriers to action. For example, implementing a three-day wait rule, where your client agrees to wait for three days before acting on a decision. For everyday spending decisions, this can help prevent your client from making spontaneous purchases that they may regret later.

Many of us are looking forward to getting back to “real life,” but there may be a few habits we hope to hold on to, such as setting aside money every month or saving up for big purchases. This past year has upended our lives in so many ways, but, for those of us who can, it’s important to look back and see what has changed for the better and incorporate that as we forge ahead.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

Disrupt your own practice

Baz Gardner’s advice in Growing your practice: How to set yourself up for success, the second session of Morningstar’s 2020 Practice Optimisation Forum, struck a chord with time-pressed advisers. The three key strategies: value proposition, aligning value to fees charged, and building a steady pipeline of high-quality referrals delivered some immediately implementable opportunities for advisers to question and build on their day-to-day practises.

In a poll run at the beginning of the session – What is the biggest internal hurdle you face in growing your business? – advisers were evenly split across three answers:

- Spending time with the right clients

- Our revenue/ fee structures

- Consistently demonstrating value to our clients

Whilst not surprising answers to Gardner, he was keen to explain how interconnected these issues are. Working through these issues are fundamental building blocks to driving growth in any advice practice.

Value proposition: never done and continuously improving

A value proposition doesn’t stand alone and Gardner suggests it’s the most important thing to get right.

“Your value proposition is never done. It should continue to get better. Once a firm thinks they’ve got it right, is when we see stagnation set it.” It’s an opportunity to keep improving and perfecting how you articulate the value you add to your clients.

Some of the simplest changes can drastically alter the profitability of a business; for example bringing to the forefront the ‘implied value’ of what you provide clients. As advisers, it’s crucial to have a general value proposition when you begin your engagement, becoming an increasingly more specific value proposition as a prospect becomes a client. Key to this is exploring their objectives, needs and wants, to really get to know what they hope to achieve. Gardner noted that this element of relationship-building hinges on specific, emotionally resonant language, and appeals to the truly human needs of a client beyond returns.

Part of developing these targeted value propositions is accountability, and the partnership nature of the advice relationship. Being not just a sounding board but a source of objectivity is foundational to the success of an adviser-client relationship – which includes setting and managing transparent expectations from the start. “We’re professional nags and we’re going to protect you from bad decisions – we expect you to take it seriously,” Gardner said. As a result, he emphasises the importance of establishing what kind of partnership style your prospective clients expect from their adviser – a key step in engagement sequencing that sets the tone for the rest of the relationship.

Pricing models: every adviser I’ve met underestimates the value they provide, it’s just a case of by how much

What’s a good pricing model? Gardner suggests “one that charges enough, with the right people.” And one that allows for the charging of additional value with additional commercial exchange. This means a profitable, sustainable practice with sufficient price tension, therefore allowing adding value where possible. What a sustainable pricing model shouldn’t do is surprise a client.

If you were having a pool built in your garden and the contractors hit bedrock, they wouldn’t carry on regardless. There would be a consultation, an option to continue or not and a clear disclosure of the additional cost. Complexities and additional work as part of the advice process is no different. That’s why having a clear pricing structure and fully briefing clients before they agree to a service not only allows for a clear articulation of value and services, but establishes and maintains trust as well – leading to longer, richer client relationships.

Gardner suggested a base retainer fee to be set and charged annually, particularly in light of the Hayne Royal Commission. Importantly, he also noted that advisers should at charging additional fees where they deliver additional value: ensuring clear benefits for both parties. Again, he noted that explicit clarification of what fees are charged for is integral to ensuring happy clients.

Referral pipeline: your business – an expression of you

Finally, Gardner spoke about how to grow a client base and finding the right clients. Rather than simply looking for potential paying clients, he looks at potential clients whose goals and values are aligned to how he delivers advice – therefore enabling you to serve more clients, better. “Meaning is one of the five things I value most in my life,” he said, “so my relationships need to have meaning.” In creating these deep relationships, word-of-mouth referrals from highly engaged clients can become a key source of organic growth – in Gardner’s estimation, 2-3%.

Baz suggested adopting a ‘go-maybe-no’ traffic lights system to consistently ensure you’re focusing on clients most likely to result in successful, fulfilling, long-term relationships.

And if you’re getting all these moving parts right, here are some final words from Gardner: “the money that they pay you will never come anywhere near close to the value you’re creating, and the impact on their lives.”

This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 1800 951 999.

The changing nature of active management

by Daniel Needham, Global CIO & President, Morningstar Investment Management

Key Takeaways

- Active management may not be in decline, rather the type of active management is changing to benefit active asset allocation. This presents investment opportunities for long-term asset allocators.

- Research shows that investors need to not only be active to outperform; they need to be patient.

- Long-term investing can be psychologically challenging, so it’s important investors have an adviser to keep their focus on what really matters.

All Investing is Active Investing

The move to passive investing has been a powerful trend, but to date has focused on security selection. In this context, passive refers to the replication of a market capitalisation-weighted index, while active may describe everything else. The same principle may apply to asset allocation, with passive classically defined as holding the entire investable market in proportion to the abundance of each part.

Clearly, few, if any, investors proportionally own every investable asset.[1] Therefore, almost every investor is active on some level. Furthermore, replicating an equity index such as the S&P 500 is therefore not strictly “passive” since trading is required to match the constituents of the index[2]. In this sense, the connection between buy and hold investing and passive investing can be misleading.

When we look at how assets are invested through more accurate definitions, we believe the share of actively managed assets hasn’t declined, as much as shifted, from security-selection to asset allocation.

That is, those buying exchange-traded funds (ETFs) aren’t buying them for keeps. They’re using them to express an active investment decision (sometimes to meet a client need) and often trading them frequently, invalidating the term “passive.”

On balance, this shift in active management increases the opportunity to outperform, we believe, for investment managers who are able to take broader views on asset classes, sectors, industries, and other characteristics. In turn, this may increase the opportunity for investors who are patient.

Shorter Time Horizons Hurt Investors

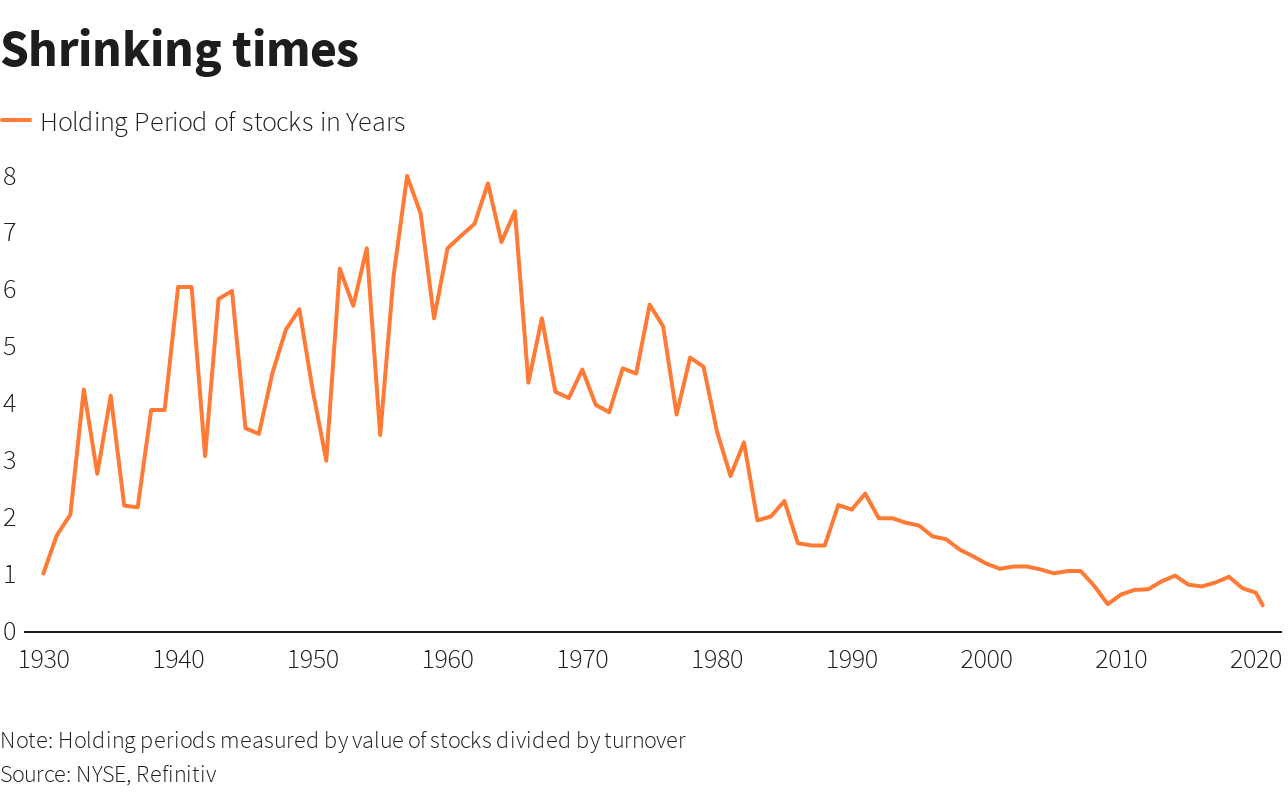

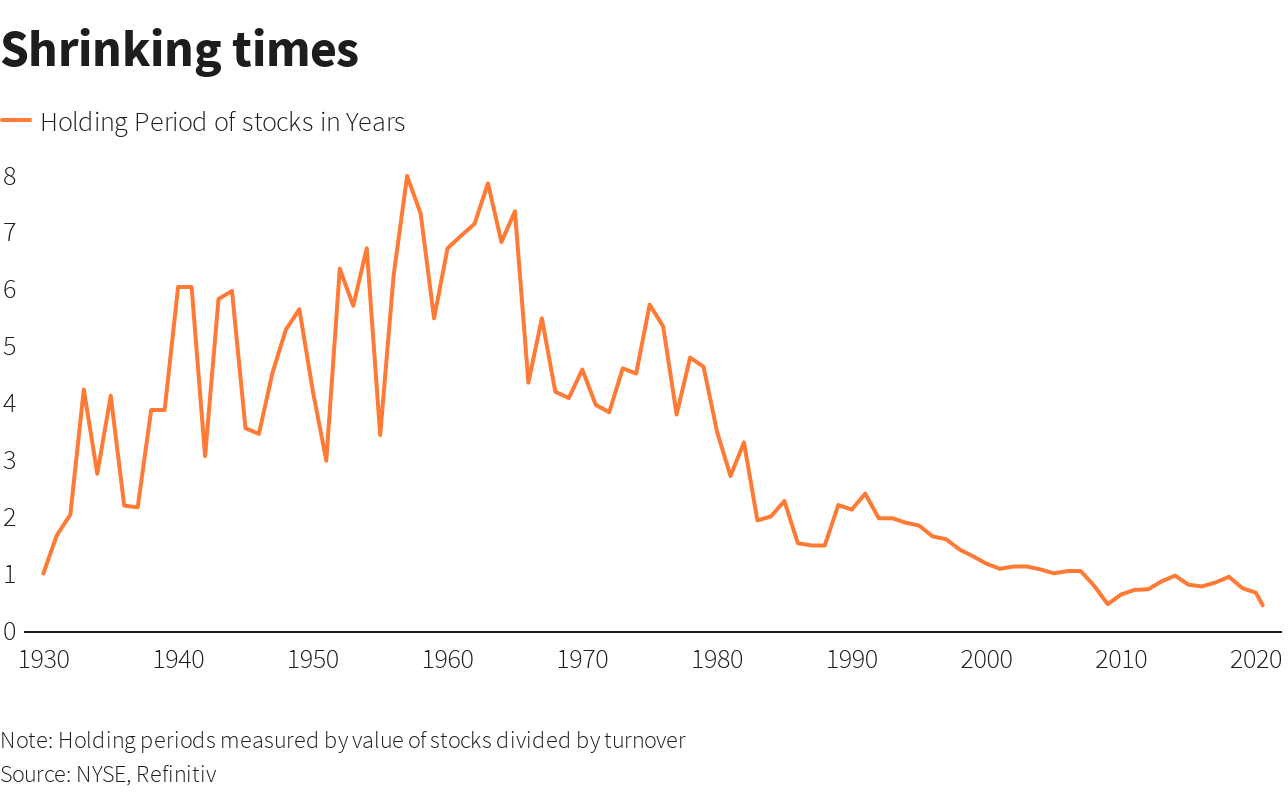

Time horizon turns out to be critical for taking advantage of investment opportunities for truly active management and receiving the benefits of compound interest—benefits that are hard to overestimate.[3] Yet, this observation contrasts with the fact that average holding periods continue to fall. Holding periods have arguably been shortened by the rise of passive management, which appears to be a contradiction given passive funds’ low turnover rates.

Exhibit 1: The reduction in holding period. Source: NYSE, Refinitiv. Note: Holding periods measured by value of stocks divided by turnover. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-short-termism-anal/buy-sell-repeat-no-room-for-hold-in-whipsawing-markets-idUSKBN24Z0XZ

If index-tracking holdings aren’t frequently buying and selling stocks, how could they contribute to shortening horizons? Because they themselves are being bought and sold. With the rise of lower-cost investment vehicles that can be traded like individual stocks, ETF volumes have risen to meaningful proportions of the market activity relative to their size. Still, it has been estimated that only about 10% of ETF volumes leads directly to the creation/redemption of shares.[4]

Despite this, it does appear that this turnover and activity impacts the underlying securities,[5] with higher volatility and turnover for stocks included within ETFs amplified by arbitrage activity—often impacting sectors, countries, industries, styles, or themes.[6]

This presents an opportunity, through active asset allocation of sectors, industries, and countries across equity markets, and for bottom-up investors that can take more active risk by including focused exposure to these areas. While the game may be getting harder in the more narrowly defined subsectors, it may be an opening for those with a long time horizon and a high active share.

By Definition, You Must Do Something Different to Outperform

According to Sir John Templeton, one of the great investors of the 20th century, it’s impossible to produce superior performance unless you do something different from the majority.

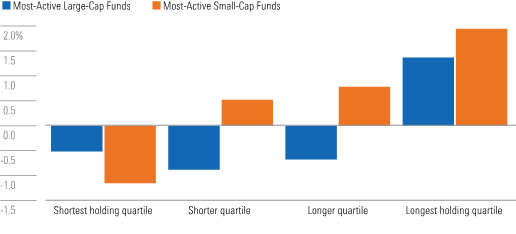

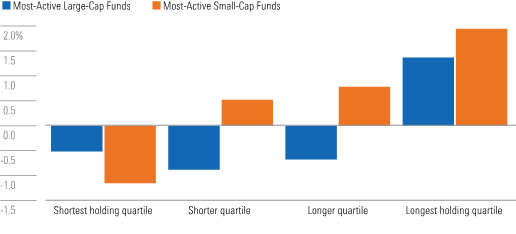

Academics call this “active share,” which is loosely defined as how different an investment strategy is from its benchmark. High active share should not be interpreted as having a higher likelihood of outperformance on its own. Like all things, one should be cautious in drawing conclusions from a single metric. On this point, author and academic Martijn Cremers[7] identified that funds with high active share and low turnover tended to do better on average. This makes sense to us.

Exhibit 2: More-active strategies held for the long run tend to outperform. Source: Cremers, M. 2016. “Active Share and the Three Pillars of Active Management: Skill, Conviction and Opportunity.” See online appendix at https://papers.ssm.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id-2891047

In our opinion, while certain strategies with lower active share and higher turnover can and do outperform, for fundamental investors time horizon seems to be the road less travelled. This concept of patient capital has been described as time horizon arbitrage and is tied to the idea of limits to arbitrage. In other words, patient investors may reap rewards—these rewards are available to any investor, but in practice go to only those who do what it takes.

Arbitrage Comes in Different Forms, Including Time Horizon

Arbitrage typically refers to different prices set for the same asset, a condition that generally requires not enough market participants seeing the big picture. The astute investor can buy at the lower price and sell at the higher one, keeping the difference.

Once, arbitrage involved buying something (gold, for example) at a lower price in one port, and sailing it to another port to sell at a higher price. With a large enough spread (and trustworthy enough sailors), anyone could take advantage of the price difference, but of course not everyone did.

Time horizon arbitrage is the idea that many investors are so focused on the short term, with lots of competition for investment results, that they don’t see the big picture, in this case the value of the investment for a long-term owner. Whether due to incentives or to psychology or career risk,[8] there’s a reluctance to extend one’s horizon. With all the focus on winning over the short-term, this reduces the competition for information that is only relevant over the long term.

While there are no doubt opportunities over short horizons for talented investors and traders, as the time horizon extends, competition appears to decline. The desire or need for quick results is the siren song for most investors. This presents an arbitrage opportunity for those willing to tie themselves to the mast and wait patiently for potential returns.

Bringing It All Together

While headlines decry the decline of active management, we may be seeing a change of active management from purely security selection to active asset allocation. This utilises portfolios of stocks, principally ETFs, rather than the underlying stocks themselves. The rise of passive management may imply less activity and longer holding periods, however the opposite may be occurring.

With the rise of active asset allocation through ETF trading, we see an opportunity for asset managers willing to be different, taking a long-term view. As the security selection asset manager universe shortens their time horizon and increase their activities, the opportunities may well be in doing the opposite—fishing where the fishermen aren’t.[9] Reinforcing one of the few durable investment advantages—a long-term investment horizon.

We think this changing nature of active management is therefore an opportunity and an advantage for us at Morningstar Investment Management. Our investment process is designed to opportunistically buy assets and patiently hold them until they appreciate. At times this means that we are well out of step with markets as we wait for prices to return to their long-term fair values, but we believe that we will significantly help investors meet their goals in the long run.

Of course, we can’t do this without their help. Changing strategies midstream can destroy value for investors because it often means selling low and buying high—something commonly referred to as “chasing returns.”

Financial advisers can help clients stay the course by reminding them of the big picture and keeping their focus on the long term.

[2] “Being passive” is in fact still an active choice. As Lasse Pederson pointed out, even “passive” managers of indexes are required to trade[2] due to buy-backs, dividends, re-constitutions and corporate actions, often with active investors on the other side. This isn’t talked about often but could be argued as a potential source of alpha. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2469/faj.v74.n1.4

[3] Albert Einstein supposedly said that compound interest was the eighth wonder of the world, and even modest returns compounded over very long time periods turn into large sums. Legendary investor Warren Buffett said his life has been the product of compound interest.

[4] In the BlackRock’s October 2017 Viewpoint, they point out that the average creation/redemption was 11% of secondary daily ETF flow and 5% of all US stock trading.

[5] https://www.troweprice.com/content/dam/ide/articles/pdfs/2019/q3/the-revenge-of-the-stock-pickers.pdf

[6] This potentially increases non-fundamental information and reducing efficiency. The more trading of baskets of stocks via ETFs, the more this can impact prices of the underlying basket of stocks. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w20071/w20071.pdf

[7] Who coauthored a 2009 paper that introduced the active share concept, and identified in a 2016 paper the relationship between active share and holding periods.

[8] The challenge is that most arbitrageurs manage other people’s money, and the fund manager may be fired before their long-term investments deliver results. The irony of the lack of competition for long-term investment ideas due to the institutional limits to arbitrage is that the benefits of compounding returns is best over very long horizons.

[9] An expression that’s a clever contrarian twist on Charlie Munger’s advice to fish where the fish are, borrowed from Jeremy Hosking, an outstanding investor of the eponymous Hosking Partners LLP.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

How can advisers help clients through market anxiety?

The market volatility in the second half of 2020 can make even the most seasoned of investors cautious.

Hesitation to trade during a downturn, however, creates an interesting dilemma: Investors are afraid to lose money, yet downturns can provide great opportunities to buy stocks at a discount. So, how can advisers help their clients calmly and thoughtfully evaluate when to buy? We believe that proper framing–how advisers describe a situation–can play a beneficial role.

3 approaches to calming investors’ market anxiety

In our experiment, we sought to understand how market downturns can affect investors’ decision-making. Specifically, we were interested in whether particular pieces of advice from a financial adviser could differently affect investors’ engagement with the market during increased volatility.

The experiment included an online sample of 880 Americans (representative by age, gender, and ethnicity), and took place in late May 2020–as markets began to calm.

The experiment’s design was simple. To ensure that our participants were aware of the market volatility, we had them read about the downturn of global stock markets with the onset of the novel coronavirus pandemic. They imagined receiving advice from their financial advisor on how to best manage their assets during market volatility in one of three forms:

- Historical performance, where the advisor framed the market downturn as a path to increase the value of their investments,

- Story, where the advisor framed the market downturn itself as a reason to stay in the market, and

- Opportunity, where the advisor framed the downturn as an opportunity to buy a stock at a discount.

Participants then decided on changes they’d make to their portfolios: either sell their equity investments, invest more in the stock market, or make no changes. We also included the option “make no changes due to having no equity investments” to omit non-investors (removing 105 participants). Only 48 participants decided to sell their investments (a sample size too small for meaningful comparisons), so we grouped them with those who decided to make no changes in order to form a “did not buy” group.

This study turned up three main findings:

- There’s power in seeing increased volatility as an opportunity. Most people preferred to either stay put or sell when they faced the story and historical performance conditions. Only when the situation was phrased as an opportunity did the majority of people buy additional stock.

- The active stay active. Across all forms of the experiment, participants who self-identified as active investors were approximately 2.4 times more likely to want to buy during a downturn compared with people who didn’t view themselves as investors or those who saw themselves as investors but are not making new investments.

- Emotions matter. Participants who reported experiencing positive emotions during the pandemic were more likely to purchase additional assets across all three forms of the experiment.

These findings suggest that during a downturn it may be more beneficial to help clients reframe their thinking so they feel positive about investing, rather than to simply encourage them to purchase.

Multiple paths through market anxiety

When the markets grow increasingly temperamental, it’s natural for investors to get nervous. There are, however, good reasons to weather the storm.

Our research shows that clients can benefit from market swings if they see downturns as a blessing, not as a curse. For anxious clients who have the resources to invest but remain hesitant, encouraging them to see increased volatility as an opportunity to earn a profit rather than as a reason to run can be a successful growth strategy.

This article includes research from Morningstar behavioural researcher Sarwari Das.

Since its original publication, this piece may have been edited to reflect the regulatory requirements of regions outside of the country it was originally published in. This document is issued by Morningstar Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 54 071 808 501, AFS Licence No. 228986) (‘Morningstar’). Morningstar is the Responsible Entity and issuer of interests in the Morningstar investment funds referred to in this report. © Copyright of this document is owned by Morningstar and any related bodies corporate that are involved in the document’s creation. As such the document, or any part of it, should not be copied, reproduced, scanned or embodied in any other document or distributed to another party without the prior written consent of Morningstar. The information provided is for general use only. In compiling this document, Morningstar has relied on information and data supplied by third parties including information providers (such as Standard and Poor’s, MSCI, Barclays, FTSE). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, neither Morningstar nor its third parties accept responsibility for any inaccuracy or for investment decisions or any other actions taken by any person on the basis or context of the information included. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Morningstar does not guarantee the performance of any investment or the return of capital. Morningstar warns that (a) Morningstar has not considered any individual person’s objectives, financial situation or particular needs, and (b) individuals should seek advice and consider whether the advice is appropriate in light of their goals, objectives and current situation. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at morningstarinvestments.com.au/fsg. Before making any decision about whether to invest in a financial product, individuals should obtain and consider the disclosure document. For a copy of the relevant disclosure document, please contact our Adviser Solutions Team on 02 9276 4550.

Building a modern advice practice

Understanding and positioning the value of advice has long been a point of tension for advisers – arguably even more so as the financial landscape changes. Whether those changes be related to a changing client demographic, more regulatory scrutiny, or dare we say it – a surprise pandemic. Morningstar’s Deborah Graham lead this discussion in Building the Modern Advice Practice of the Future, the final session of the recent Practice Optimisation Forum.

Graham was joined by Recep III Peker (Investment Trends), Grant Chapman (Fintech Financial Services) and Phil Anderson (Association of Financial Advisers). Attendees were welcomed to the digital session with a poll that would then dictate the topic of the day: a choice between ‘making advice affordable – is there a role for scaled advice?’ and ‘the value of the technology stack’. Scaled advice had the edge with 59% of the votes, sparking a thoughtful discussion among the panellists.

Aligning value to appetite: Finding opportunities in scaled advice

Recep III Peker cited a July 2020 survey finding that people actively seeking advice said, on average, they’d expect to pay $360 for financial advice. Taking rent, overheads and other costs of running a business in account, Peker gave a ballpark figure for what advice generally costs – closer to $3000-$4000, therefore revealing significant dissonance between the perception and actuality of pricing. He suggests that scaled advice is the gateway to building a broader, comprehensive advice relationship – providing the opportunity to educate clients on the value of both advice and the advice pricing models.

“If you get personal advice, it’s like jumping into marriage straight away. With scaled advice, it’s more like dating. There are three times as many people who want to start with scaled advice, but 93% of these people are happy to get comprehensive advice down the track. Essentially, scaled advice can serve as a strong hook when it comes to addressing the affordability of advice.”

Phil Anderson agreed, but noted industry challenges that advisers may face as they seek to incorporate scaled advice in their service offerings. “Scaled advice is going to be critical to keep advice affordable for everyday Australians. Research says the unadvised aren’t willing to pay, but existing clients are paying substantial amounts of money and are getting great value out of that… we’re in a difficult position because we see a lot of opportunity with scaled advice but we need more regulatory certainty. And we need to have the opportunity for advisers to improve their processes and push forward to really rationalise the process, to add value at every stage for the client so they’ll want to come back.”

In discussing value, having a clear picture of your customer or intended audience can shape your practice. “What is your target client segment?” Grant Chapman asked. “If you’re dealing with Generation X or a younger cohort, they might be used to doing things online and getting things quite cost-effectively, you’d need an offer that appeals to them. Providing a scaled advice solution, and particularly using technology – I can’t emphasise enough how much technology needs to be integrated for efficiencies and delivery. You may use scaled advice to get initial business with a younger group, and that becomes a journey as their life evolves.”

Positioning the cost of advice

“It’s a real tension for advisers,” said Chapman. “How do we actually deliver what the client needs, whether that’s scaled advice, or where every area of advice is comprehensively addressed with a lot of cost and time involved?… We have to re-educate our clients and deliver the information to them in a way that they understand the value that’s being provided to them. I think when clients actually do see that, and go through the process of understanding, they’re more willing to pay for that advice.”

Similarly, the efficiency theme doesn’t just apply to the scaled advice realm – nor is it just about creating day-to-day efficiencies in your practice. “Right now for financial planners, the true opportunity to make money, is from your ability to retain a larger client book. So anything that makes you more efficient is really powerful. If you’re sitting behind your computer picking stocks every day, that’s time you didn’t invest in doing the client update and showing them value to invest another year,” said Peker.

How do clients want to be engaged?

Tailored communication with clients may not be reinventing the wheel, but research shows that this foundational piece remains hugely important to clients across the board. “Satisfaction with financial planners is at the lowest level we’ve observed in ten years,” said Peker. “And this isn’t because financial planners aren’t managing their clients’ investments well. If you ask clients to rate their financial planner on investment expertise and investment selection, it’s actually at a near-time high, because for a lot of people their adviser told them to stay in the market. However, what’s dragging the satisfaction score down is the piece around how frequently I get contacted, ability to explain investment concepts and so on.” Delivering financial education, engaging content and therefore creating a two-way relationship with clients has become a cornerstone of the modern advice practice.

Social media, video and intuitive online portals have been everywhere in 2020, and the advice sector is not immune to these trends. With different mediums appealing to different audiences, the panellists also spoke to how these methods can best convey an adviser’s well-thought-out messaging.

Financial planning software and emerging fintechs also rated a mention in the client engagement space: “you can really personalise the experience and make the client feel in control of the process… However, we need regulatory certainty so advisers know how to incorporate this into their processes,” said Anderson.

It’s apparent that though the methods may change, proactive engagement remains a reliable tactic that endures through industry changes. And in doing so, advisers are better positioned to plant the seeds for long-running client relationships.