Rules as Tools: Using Heuristics to Help Empower Financial Success

By Ryan Murphy, Global Head of Decision Sciences

Key takeaways

- We studied commonly used rules of thumb in four financial categories (saving, spending, investing, and debt management). Some rules were weakly correlated to better financial well-being—that is, those who used a rule tended to report they were more on track to meet their financial goals—while for other rules, the opposite was true.

- Across the categories, spending rules appear to be the most strongly related to financial well-being, largely because we believe they may help investors handle complex decisions easily and make constructive behaviours automatically.

- We believe our research suggests that investors should discuss their financial rules of thumb with their adviser, who can help guide and promote their effective use.

Simple Tools Aren’t Always So Simple to Use

People often use simple mental shortcuts, also called heuristics or rules of thumb, when they make everyday decisions. And while the behavioural sciences tend to focus on how these shortcuts can backfire and create biases that lead us astray, much of the time these shortcuts lead to pretty good outcomes.1 In fact, research suggests that, in certain environments, using simple rules may be more efficient than trying to use more-complex, optimised processes.23

One such environment is complex financial decisions, where simple shortcuts may lead to better decision-making. The idea of using simple rules for finances isn’t new. Many rules have been made popular by TV personalities, best-selling authors, and, now, even social media.

But can these rules of thumb improve financial well-being? We studied commonly used rules of thumb in four financial categories (saving, spending, investing, and debt management). Some rules were somewhat correlated to better financial well-being4—that is, those who used a rule tended to report they were more on track to meet their financial goals—while for other rules, the opposite was true. Across the categories, spending rules appear to be the most strongly related to financial well-being.

For those rules correlated with worse financial health, we don’t believe these to be unhelpful necessarily. Instead this shows the nature of correlations as imperfect reflections on fairly complicated situations. For example, someone using a sensible debt management rule to pay off highest-rate debt first may appear to have poorer financial health because of their debt load, but this still is a good rule of thumb. We suggest people view financial rules of thumb as context-dependent and that individuals seek the help of a financial adviser to help them tailor an arsenal of effective rules for their situation.

Somewhat ironically, guiding people to use simple rules of thumb is not always so simple. But good financial advisers can understand their clients’ needs and help them navigate complicated decisions with simple and effective tools.

Studying Rules Use, Financial Well-Being

We surveyed a nationally representative sample of 867 Americans adults5 to learn which rules people use for their financial decisions. We also measured participants’ financial well-being using the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Financial Well-Being Scale6—a standard measure of financial health.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four question sets (to keep the number of questions manageable per person), and each set focused on one topic: spending, savings, debt management, or investing. We provided a list of common rules (from existing academic, industry, and internal research) in each topic and asked participants to rank the rules by how closely they followed them when making financial decisions. We then analysed the data to identify which rules people said they used, how often they used them, and whether there were associations between each rule’s frequency of use and the individual’s financial well-being.

We also asked participants about how easy and automatic it was for them to follow a particular rule, because habit formation (known as automaticity) for certain rules might make them more effective. Research shows that habits are powerful, and findings suggest that making a desired behaviour routine can help people stick with a behaviour over the long term.7 Knowing which rules are easier to turn into habits might be useful to people who want to change their behaviours or people who want to help others make a change.

How Do Rules Correlate With Financial Well-Being?

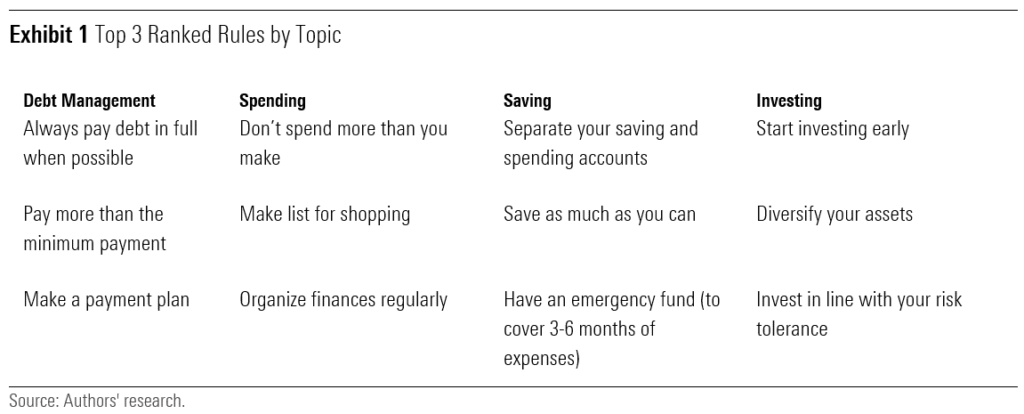

Exhibit 1 shows the top three rules that respondents ranked in first place based on “how closely [they] follow them when making [topic] decisions,” according to the survey question.

Next, we examined the correlation between the ranking of the different rules and participants’ financial well-being score to gain insight into how different rules are associated with financial health. Six rules were weakly correlated with financial well-being scores—half of them were negatively correlated, meaning people who use those rules tend to have lower financial well-being scores. Our results suggest more research is needed to show how different rules can directly improve and promote financial well-being.

Turning Heuristics Into Habits

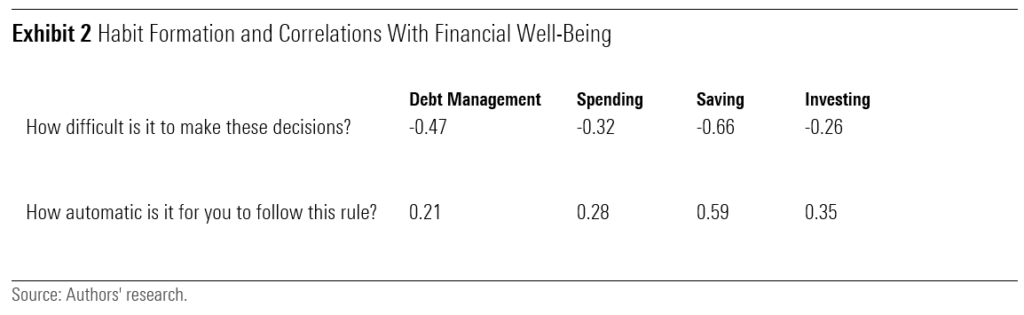

A rule can only be effective if it’s actually used. Our analysis looked at how easy and natural it was for participants to use financial rules of thumb. We first asked participants how difficult it was for them to make financial decisions for each topic, with 1 being extremely easy and 7 being extremely difficult. We weren’t surprised to find weakly negative or no correlation between someone’s perceived level of difficulty and their financial well-being score—the easier it was for a person to make these decisions, the more financially well-off they were. This effect was strongest among saving rules.

We also asked participants how automatic it was for them to follow their top-ranked rule, with a score of 1 implying that they needed a constant reminder to use the rule and 7 implying that they use the rule without thinking. Here we found some positive correlation between a person’s habitual use of a rule and their financial well-being score. Again, the effect was strongest among saving rules, suggesting that the difficulty and automaticity of saving decisions have a very strong relationship with financial well-being. And while correlations do not signify causation, the correlations do point to the importance of saving decisions for people seeking financial health.

Existing research8 on habit formation points to the importance of a few factors to make good behaviours stick:

- 1. Difficulty of the behaviour

- 2. The context of the decision

- 3. The immediate reward associated with the behaviour

When it comes to financial rules of thumb, the difficulty of the behaviour can depend on a few external factors that one might not have control over, such as level of income and expenses. However, we can exercise some control over the decision-making environment and the reward we associate with the behaviour.

For example, if a person is trying to make the rule “Save up for big purchases” into a habit, they can start by setting money aside right when they receive their paycheque. This behaviour can reduce the friction associated with the decision because it can help us avoid the temptation of spending the money later—in other words, if the money is stowed away, you can’t spend what you don’t have. This tactic also gives us a dependable cue to save our money, since we know that as soon as we get our paycheque, we should dedicate some of it to saving.

It’s also important to reward ourselves for the behaviour as soon as we complete it. The reward can be something simple and inexpensive—like splurging on a fancy coffee drink right after we complete the transfer to our savings account. The point of this step is to associate the behaviour with something that makes us happy, to encourage us to keep it up.

Rules and Habits: A Powerful Combination

Using simple shortcuts when making financial decisions might not be ideal but it may be useful given the constraints real people face every day. People often have to make financial decisions in less-than-ideal situations: they may face an overwhelming number of options, unpredictable uncertainly, intense time pressure, a lack of information, and inexperience. Of course, working with a financial adviser could minimise these challenges, but advisers can’t control their clients’ behaviours.

Our research emphasises the importance of having good financial habits. We find that good shortcuts that become good habits are more powerful than good shortcuts alone. Incorporating shortcuts that both make good sense and are easily ingrained in everyday behaviour in a financial plan could be a powerful combination to fuel investors’ goals for the long term and help empower their financial success.

[1] Statman, M. 2017. “Finance for Normal People: How Investors and Markets Behave.” (New York: Oxford University Press).

[2] Gigerenzer, G. & Gaissmaier, W. 2011. “Heuristic Decision Making.” Annual Review of Psychology, Vo. 62, No. 1, P. 451. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145346.

[3] Dimova, M. 2015. “Heuristics: A Behavioral Approach to Financial Literacy Training.” CGAP, Feb. 12, 2015. http://www.cgap.org/blog/heuristics-behavioral-approach-financial-literacy-training.

[4] Financial well-being was measured using the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Financial Well-Being Scale.

[5] The authors conducted the survey from Feb. 20, 2020 to March 6, 2020. The sample consisted of individuals with the average age of 47 years old and the average income range of $40,000 – $49,000. About 48% of our sample was male and 52% was female.

[6] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. 2015. “Measuring Financial Well-Being: A Guide to Using the CFPB Financial Well-Being Scale.” https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201512_cfpb_financial-well-being-user-guide-scale.pdf

[7] Gardner, B. & Rebar, A. 2019. “Habit Formation and Behavior Change.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. https://oxfordre.com/psychology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.001.0001/acrefore-9780190236557-e-129.

[8] Wood, W. 2019. “Good Habits, Bad Habits: The Science of Making Positive Changes That Stick.” (New York: Macmillan/Picador).